Putting Europe on a trajectory of growth, innovation and green transformation

Table of contents

Chapter 1: “Non-Europe” in banking

1.1 Introduction: Many non-financial sectors have a well-functioning EU single market

1.2 What is cross-border banking?

1.3 The European banking market is fragmented

1.4 Digitalisation could drive increased cross-border banking

Chapter 2: Benefits of an integrated banking market

2.1 Three main benefits of a single EU banking market

2.2 Estimates of the benefits from a single European banking market

Chapter 3: Barriers to an integrated European banking market

3.1 Barriers to an integrated European banking market

3.2 Four packages of initiatives to remove the four barriers

Preface

The programme for the German Presidency of the EU Council highlights two fundamental challenges for Europe. First, the economic and social repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic must be contained. Second, to support the transformations within innovation, digitalisation and green transition, thereby strengthening Europe’s ability to exercise its responsibility in the world.

Within both goals, we see a strong European banking sector playing a crucial role.

Within the first goal, the European banking sector is central in avoiding that the pandemic crisis spirals into an economic and social collapse with soaring bankruptcies and unemployment. So far, this has been avoided, partly due to the extensive rescue packages provided by the European governments, but also due to a robust capitalisation of the banking sector that could keep credit flowing to companies in distress. That is, the worst economic shock Europe has seen in decades has not materialised into a financial crisis.

Within the second goal, a strong, innovative and competitive European banking sector is a prerequisite to finance investment within digitalisation, innovation and, not least, to mobilise the necessary capital to meet the investment need of transition to a carbon-neutral economy.

However, the European banking sector does not currently live up to its full potential, as it is being bogged down by very fragmented markets. First, it deprives financial institutions of the efficiency gains of scaling their supply to a single EU banking market. Second, it hampers international competition, not allowing the best-in-class financial business models to reach end-customers throughout EU.

Thus, the time is ripe to focus on establishing a single, digital European banking market supporting Europe to exit the COVID-19 pandemic on a trajectory of growth, innovation and green transformation.

Therefore, we have engaged with Copenhagen Economics to analyse the benefits of an integrated European banking market and what is currently preventing it as well as to identify initiatives that could make it happen.

Concretely, we want to thank Sigurd Næss-Schmidt, Jonas Bjarke Jensen and Hendrik Ehmann for their work on this paper.

Executive summary

The European single market for goods and services is in many ways a story of success, and today intra-EU trade amounts to more than 30% of EU GDP.

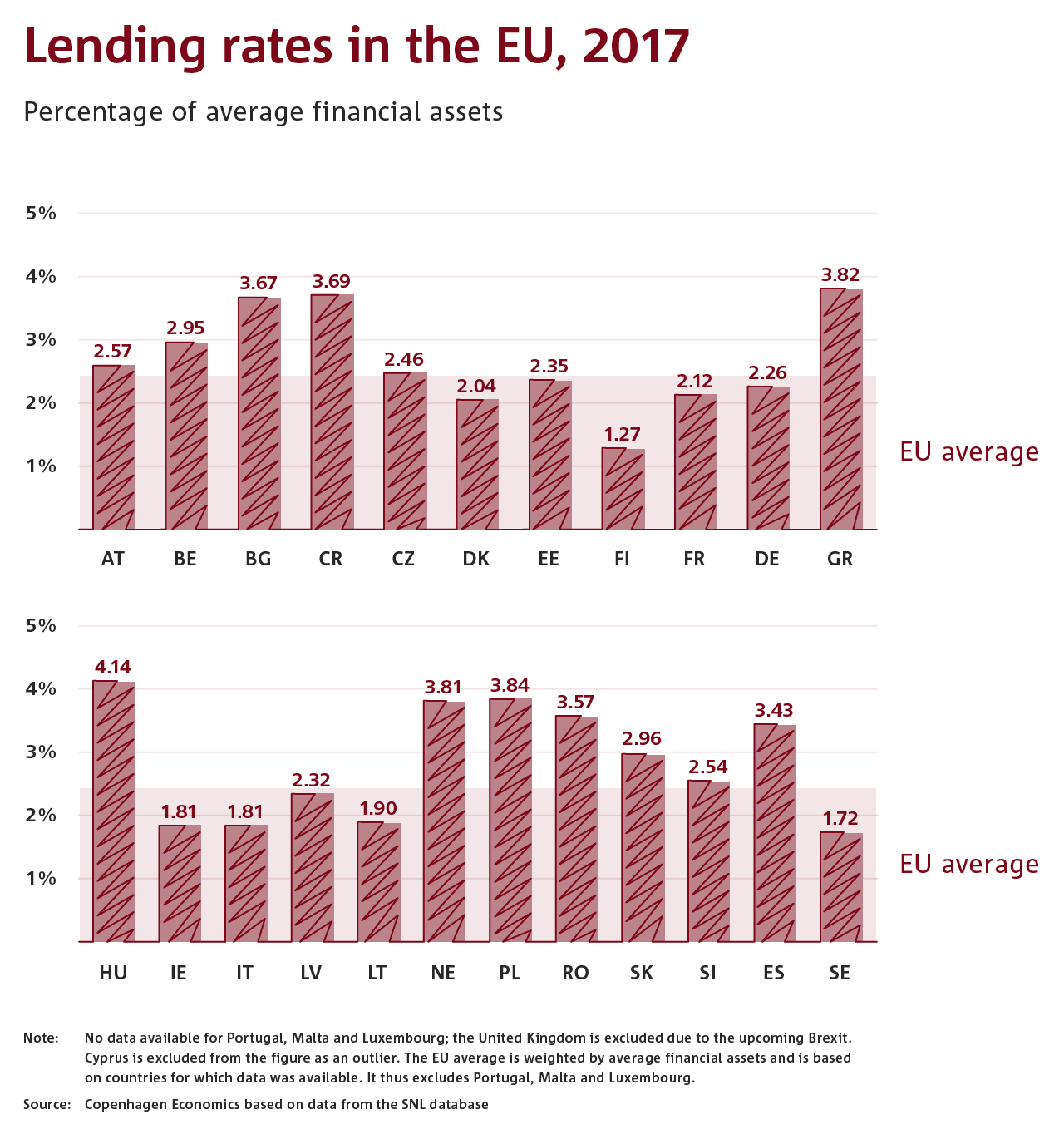

There is one noteworthy exception to this accomplishment: the European banking markets. Domestic banks often have the vast majority of the market within each country; only around 10% of banking assets are owned by foreign institutions for the median euro area country. And customers being serviced directly from a bank in another country are almost non-existing. The fragmented banking market is evidenced by high spreads in the costs of finance for businesses and households across the EU. For example, average lending rates range from around 4% in the most expensive countries to below 2% in Finland.

The differences to some degree reflect different levels of efficiency of the banking sectors, but we also attribute it to the fact that the framework conditions for providing low cost services to customers differ markedly. For example, in some countries, the process of protecting the value of loans and other business assets can be very costly and end in long and protracted negotiations as banks try to enforce their claims. These costs will ultimately have to be borne by the customers in the form of higher margins to cover for the higher costs.

Moreover, the European banking sector does not appear to be on the path getting more integrated. In fact, cross-border banking seems to be in reverse; the share of banking assets owned by a foreign bank has declined by 7 percentage points since the financial crisis and there are no signs of converging interest rates.

As a consequence, this study looks at the three key questions:

- What benefits could consumers reap if the EU could achieve an integrated banking market?

- How can digitalisation help break down barriers?

- What policy initiatives should be prioritised to deliver the internal market in banking?

Benefits of an integrated banking market

We expect that a single digital EU banking market would help European households and businesses to obtain low cost and efficient financing, supporting the ambitions of the German Presidency of exiting the COVID-19 crisis on a trajectory of growth, innovation and green transformation. Concretely, we find that an integrated banking market would lead to more efficient provision of credit through three main channels:

- Spread of the most successful business models: In an integrated market, the most profitable and cost-efficient business models would gain market shares through strengthened international competition. Copenhagen Economics estimates that this could bring about benefits in the magnitude of EUR 50-70 bn per year due to lower finance costs for European businesses and households.

- Increased economies of scale and scope: The increase in market share of the efficient exporting banks and the associated process of consolidation, would lead to costs savings due to economies of scale and scope, which is very predominant in banking; a recent empirical study finds that a 100% increase in output on average increases total costs by 86%. Using the US market as a benchmark, Copenhagen Economics estimates that larger economies-of-scale effect could bring about efficiency gains of around EUR 30-40 bn per year. At first, these cost-savings-scale, would accrue to the banking sector, however, through competitive pressure, are expected to gradually be passed on to consumers.

- Better allocation of capital across countries: An integrated European banking market would ensure better availability of credit for businesses and consumers irrespective of the state of the financial sector of their home country: This is particularly important in a crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic with very heterogeneous impact across countries.

This brings the total potential longrun benefits of a single banking market up to around EUR 95 bn per year, corresponding to a decline in costs of financial services of around 12%. Note, that the benefits are not only a matter of increased efficiency – but also a spread of the most successful business models that eventually would require a change of the underlying structures shaping financial products across Europe.

A more efficient and innovative European banking sector does not only imply a stronger credit flow to the European economy – it will also increase the global competitiveness of European banks, in line with the German Presidency ambitions of a Europe able to exercise its responsibility and interest globally.

The critical role of digitalisation to break down barriers to trade and promote new business models

The current rapid digitalisation process of the European financial markets provides a unique window of opportunity to unlock and break down historic barriers to integration. Historically, cross-border expansion has primarily been through the establishment of financial infrastructure systems in a new country, often via M&A deals. Customers being serviced directly from a bank in another country have virtually been non-existing. The reason being that physical proximity between bank and client has been a requirement – for both parties. A digitalised infrastructure could change that. For example: mobile applications and online calls can allow customers to manage their banking activities without the need to visit a local bank branch. And customers can be identified digitally at distance, e.g. through biometric technologies.

Thus, the digitalisation process increasingly gives the potential to make cross-border banking a straightforward and obvious business opportunity for efficient and innovative banks. However, there are currently a range of regulatory and legislative barriers holding back this development.

Barriers to realising the benefits of a single banking market

We have identified four main barriers that often make cross-border banking an unprofitable business case for European banks:

1) Legislation posing a direct cost to cross-border banking

A natural first step, would be to look at the regulation in place, directly making cross-border operations more costly. This includes:

- Some capital requirements punish cross-border banking, e.g. a higher G-SIB buffer for exposures within the single banking market. Also, ring-fencing of capital from subsidiaries could lock up around EUR 100 bn. in CET1 capital at European banks.

- Cumbersome cross-border banking reporting requirements, increasing the cost of cross-border operations.

- Cross-border M&A process entails high compliance costs, e.g. due to differences in national laws that govern mergers. Moreover, national supervisory authorities might tend to fend off foreign entry to avoid so-called national heroes” having foreign ownership.

2) Legislation providing an unlevel competitive playing field across borders

Banks operating in a jurisdiction with high level of taxation and strong regulation, might be discouraged from competing with banks in less regulated countries, thus impeding cross-border competition:

- National gold-plating implies that rules are implemented in a more profound manner than outlined in the EU directive. In terms of capital requirements, Copenhagen Economics expects that reducing national gold-plating could free up capital in the magnitude of EUR 100-140bn for European banks, reducing annual funding costs for European banks by EUR 11-16 bn.

- Different tax systems can give rise to competitive disadvantages for affected banks. To illustrate this, Copenhagen Economics estimates that a 5 percentage point difference in corporate tax rate can give rise to a 5-basis-points funding costs (an increase in funding costs of 3%). This is well in line with the Presidency focus of ensuring that tax burdens are being fairly distributed across the EU.

3) Barriers to digitalisation of the banking sector

As described above, digitalisation could by itself be a catalyst for increased cross-border banking. However, the digitalisation process in the banking sector is limited by:

- Different know-your-customer (KYC) rules: Cross-border banking is currently limited by different KYC rules and standards in each country.

- Non-harmonised regulation of crypto assets provides uncertainty regarding the legal framework. This could hamper crypto assets distribution across the EU, not allowing businesses and households to reap the full benefits of the technology. In addition, for innovators, an incoherent legal framework prevents sufficient scale in developing new crypto asset solutions.

4) The design and properties of products sold in each country are different

The design and properties of banking products differ between countries in EU. When banks supply financial services cross-border, they have to be adapted to these country-specific conditions. This means that banks cannot simply resell their products, posing limitations on the beneficial effects of economies of scale in banking.

To allow the most efficient financial business models to be supplied across EU, governments need to address underlying structures that currently entail much greater risks in credit provision in some regions. In case of default, it is too difficult or costly to access underlying assets, hence lending will not be provided or only at very high rates.

These underlying structures entailing high risks can also explain why, despite extremely low policy rates, we still see average lending rates of around 4% in some countries. Put in other words, if these underlying structural issues are not addressed, the current very expansionary monetary policy cannot be converted into real drivers of recovery for the European economy.

This has become even more relevant in face of the COVID-19 crisis, which could compound these costs, e.g. of having insolvency laws that provide lengthy and costly procedures to deal with default. That is, banks could retract even more from providing necessary lending as the pandemic is increasing the financial risks of defaults.

Thus, we suggest that the recovery programmes put in place by national governments address these factors to maximise the contribution that the banking sector can deliver in putting the EU economy back on track.[1]

Chapter 1

“Non-Europe” in banking

1.1 Introduction: Many non-financial sectors have a well-functioning EU single market

Since the creation of the EU, establishing a single market for goods and services has been a core aim. In several ways, it has also been a story of success; a long range of different initiatives have managed to harmonise national legislation and remove other regulatory obstacles to the single market and today intra-EU trade for goods and services amounts to more than 30% of EU GDP. [2] The European commission has highlighted the single market as among the greatest achievements of the EU and a deepening market integration remains a priority for EU policy makers. [3]

The effort to create a single market follows naturally from the many economic benefits a single market entails, as documented in numerous studies :[4]

- Companies can reap costs savings from supplying to a much larger market due to economies of scale and scope.

- Increasing competition on a European level, improving efficiency

- More variety in different products and services provided to customers.

However, one noteworthy exception to the success of the single market remains: the European banking markets. As will be documented in this chapter the banking markets remain fragmented across the EU, with domestic banks largely dominating the supply of services to consumers in the given country.

The rest of the chapter is structured as follows: First, we outline the scope of this paper, including the two most common definitions of cross-border banking used in empirical research (section 1.2). Second, we document how the EU banking market is fragmented (section 1.3). Finally, we briefly discuss how digitalisation – if not obstructed by regulatory barriers – could ignite a process of market integration (section 1.4).

1.2 What is cross-border banking?

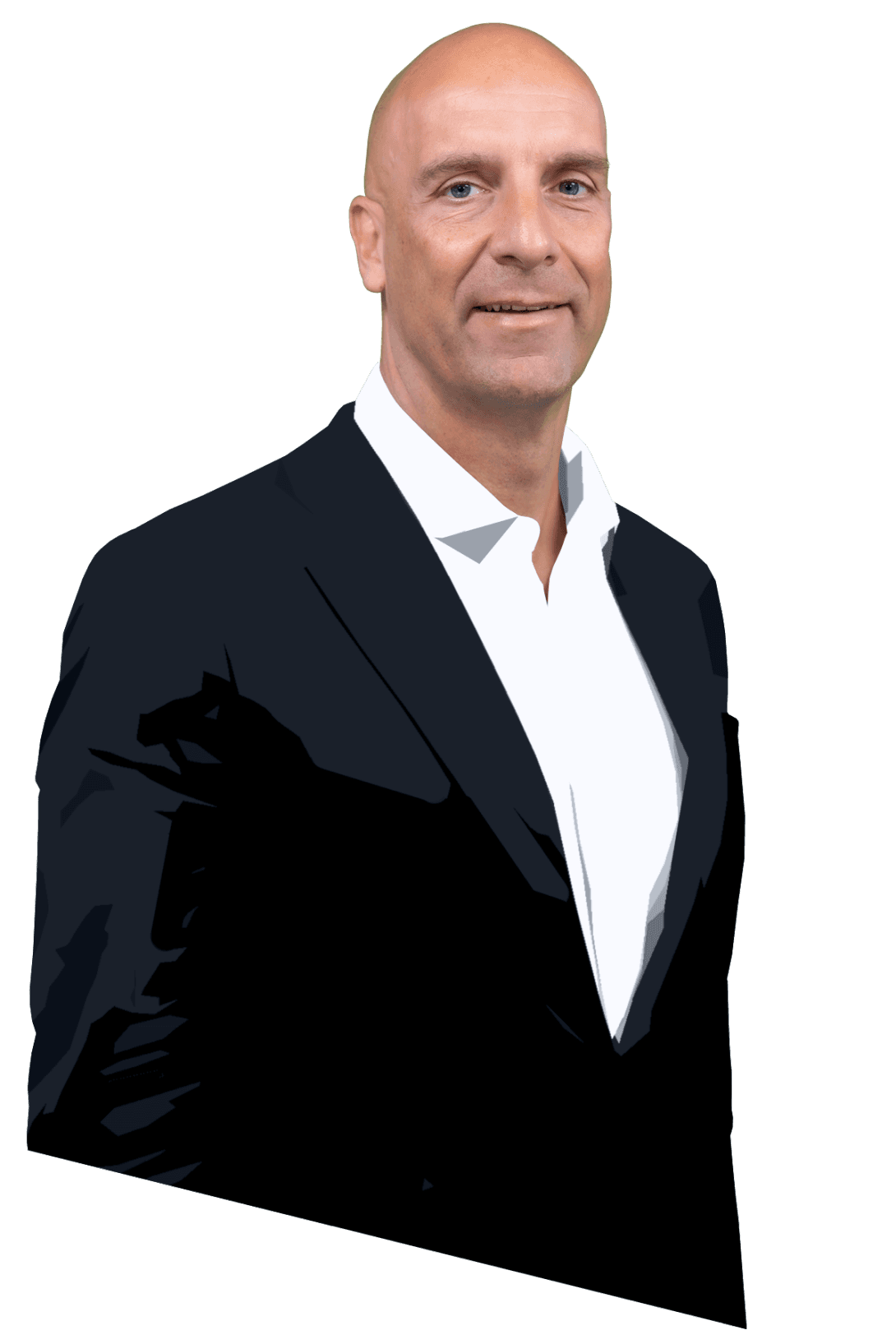

Generally speaking, banks can provide services across borders in two ways: directly or indirectly, cf. Figure 1:

- Direct cross-border banking refers to the provision of financial services directly from a branch (or financial company) located in another country. This type of cross-border activity has historically been low in the European Union (EU), primarily because geographical proximity and personal contact to customers have been important factors in banking.[5]

- Indirect cross-border banking refers to the provision of financial services by a bank in another country via subsidiaries and branches located in the country of the customer. For instance, services provided to Italian customers by a German bank via a branch or subsidiary located in Italy are counted as indirect cross-border banking.

The choice between supplying through a subsidiary or branch impacts the supervision of the bank. Subsidiaries are considered as a distinct legal entity and are thus supervised by the host country, whereas most branches are liable to regulation in their home country.[6] Consequently, banks aim at conducting indirect cross-border banking through branches, as this limits the costs of being subject to full-scale regulation in several countries. However, for historical reasons many banks still operate with subsidiaries in several countries. Also, some regulatory barriers require banks to operate with a subsidiary. For example, if a non-euro country wants to conduct indirect cross-border banking within the euro area, it requires the establishment of subsidiary in a euro area country.

Box 1 Focus of this paper

In this paper, we focus on core banking, i.e. services directly related to deposit taking and credit provision. This includes mortgage loans and other retail loans, loans to corporates and loans to small and medium-sized enterprises. This means, we exclude payment services, investment banking (trading in debt and equities), and asset management.

1.3 The european banking market is fragmented

1.3.1 Direct cross-border supply of retail financial products remains almost non-existent

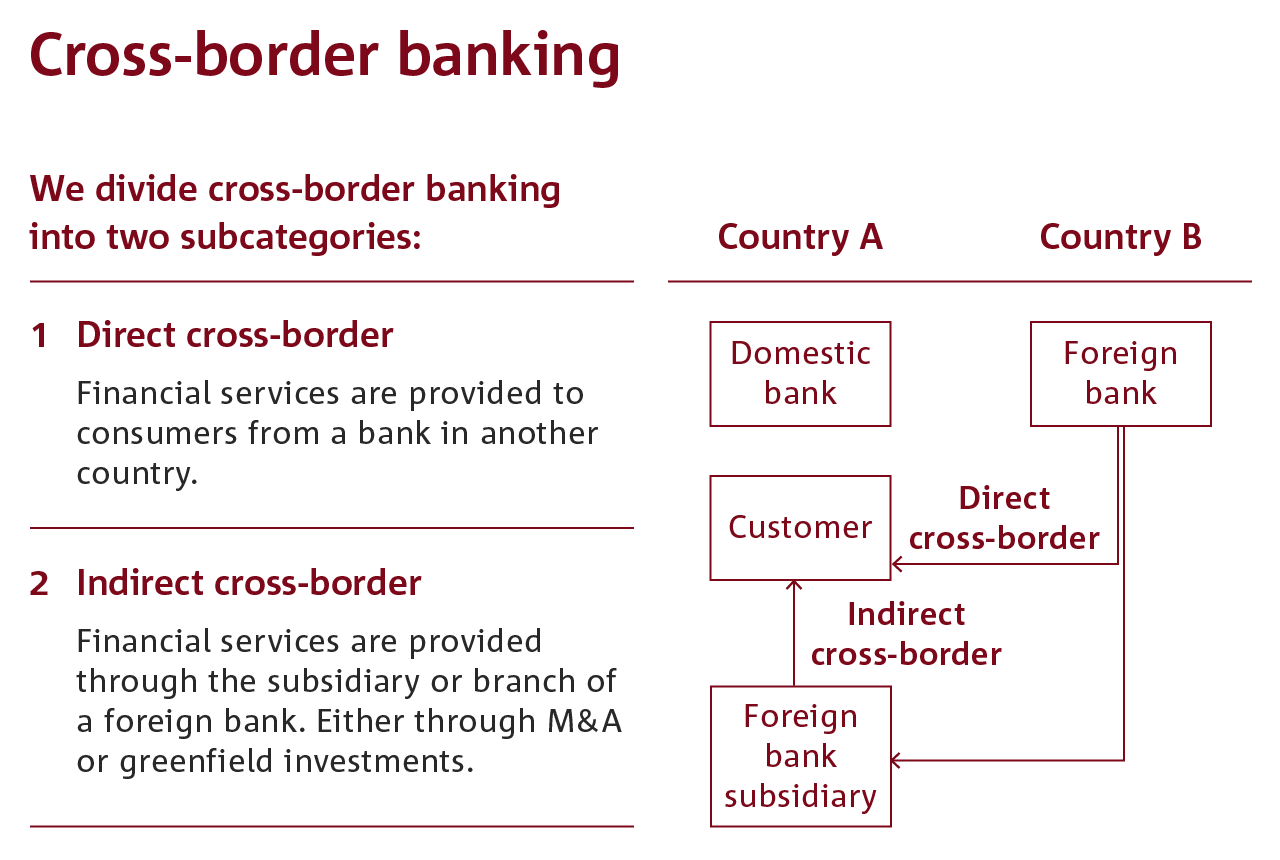

Direct cross-border supply of financial services is very limited within the EU; only 8% of EU citi-zens have bought a financial product or service in another EU country, cf. Figure 2.

Of this, the most common direct cross-border supply was the provision of current accounts (around 3%). This is however likely driven by people moving abroad and keeping their current account in their home country – thus hardly serving as an indicator of integration in European banking.

Moreover, there is little indication for a declining fragmentation in banking markets. Between 2011-2016, the percentage of people that have bought financial services in another EU country has increased by merely 2 percentage points.

1.3.2 Limited indirect cross-border banking

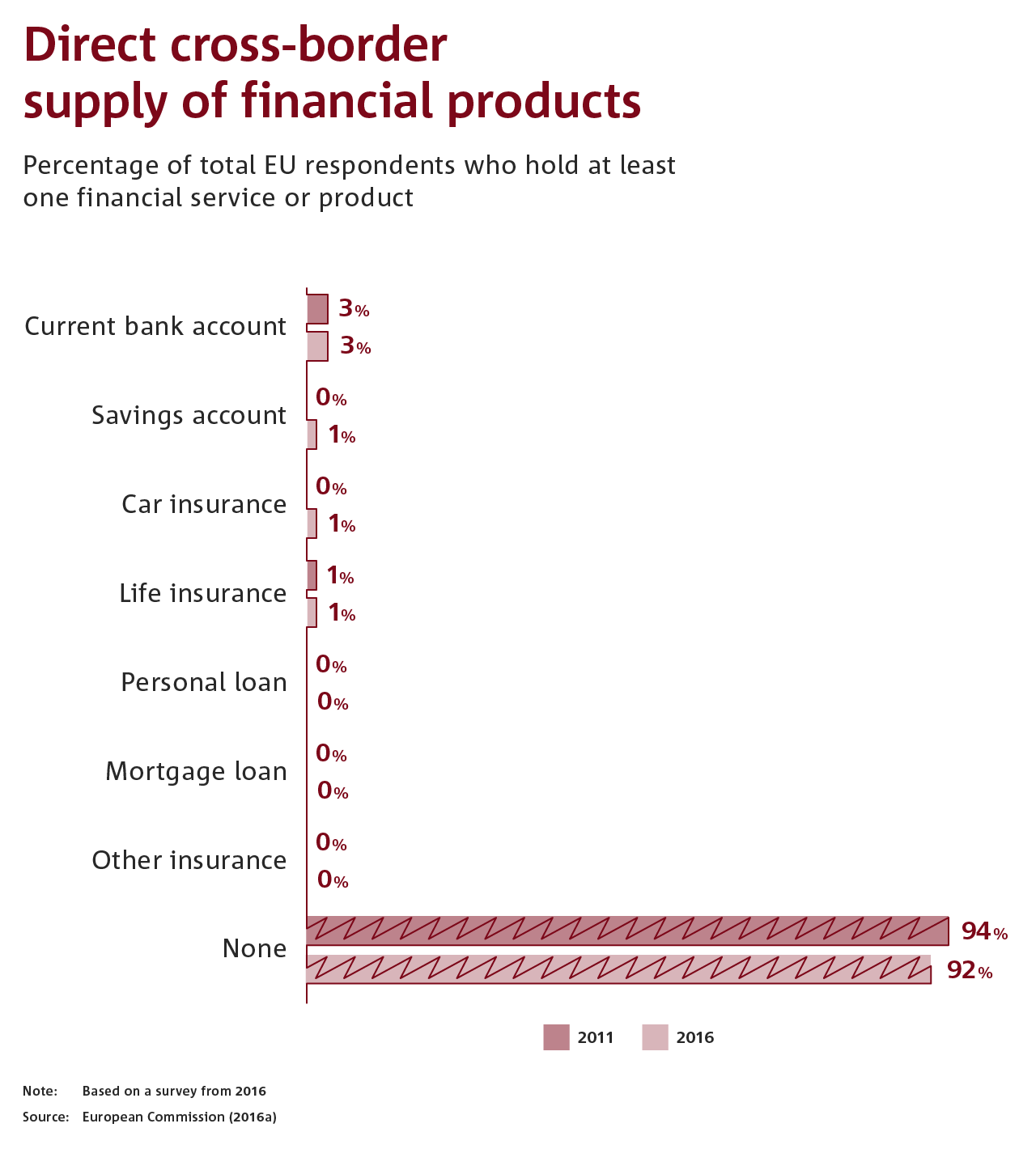

Indirect cross-border banking also remains limited. In most of the EU countries, the majority of the banking assets in the country are held by domestic credit institutions. For the median euro area country only around 10% of assets are held by a subsidiary or branch of a foreign bank. This is in fact a decline compared to around 17% in 2007 (cf. Figure 3).

This decline in cross-border banking, can be seen in the light of a rise in non-performing loans and stricter capital regulation in the aftermath of the financial crisis, which has induced banks to decrease their leverage ratios.[7]As banks tend to discard foreign assets first (also called the flight home effect), this particularly affected banks’ cross-border activity.[8]Also the lack of capital requirement waivers could have been in play here, as will be discussed in chapter 3.

The typical cross-border expansion is carried out through M&A deals, rather than greenfield investments as most European banking markets are perceived as somewhat “over-banked” and consolidation, rather than establishment of new banks, is required. Therefore, a low level of cross-border M&A deals within the euro area is worrying. Between 5% and 19% of M&A transactions within the Euro area were across borders between 2000 and 2016. In comparison, between 31% and 53% M&A deals in the US in the same period were cross-state.[9]

1.3.3 The fragmented banking markets give rise to large interest rate differentials

The limited degree of cross-border banking in the EU is mirrored by large interest rate differentials across member states; the difference between the country with lowest average interest rates (Finland) and highest (Hungary) lending rates is close to 3 percentage points, cf. Figure 4.

1.3.4 The nature of the products sold in each country is inherently different

The large interest rate dispersion partly reflects that banking services supplied in each country are inherently different products (will further be explored in chapter 3, when barriers to cross-border banking are outlined).[10]This relates to:

- Differences in legislation governing the products including consumer protection laws and insolvency laws as well as supervisory and regulatory differences due to the divergent implementation of EU directives.

- Different structure of products related to cultural/historical aspects. In Germany, for instance, mortgages are traditionally fixed-rate loans on the balance sheet of banks, whereas in Sweden, customers often have variable interest rate mortgages provided through specialised mortgage institutes.

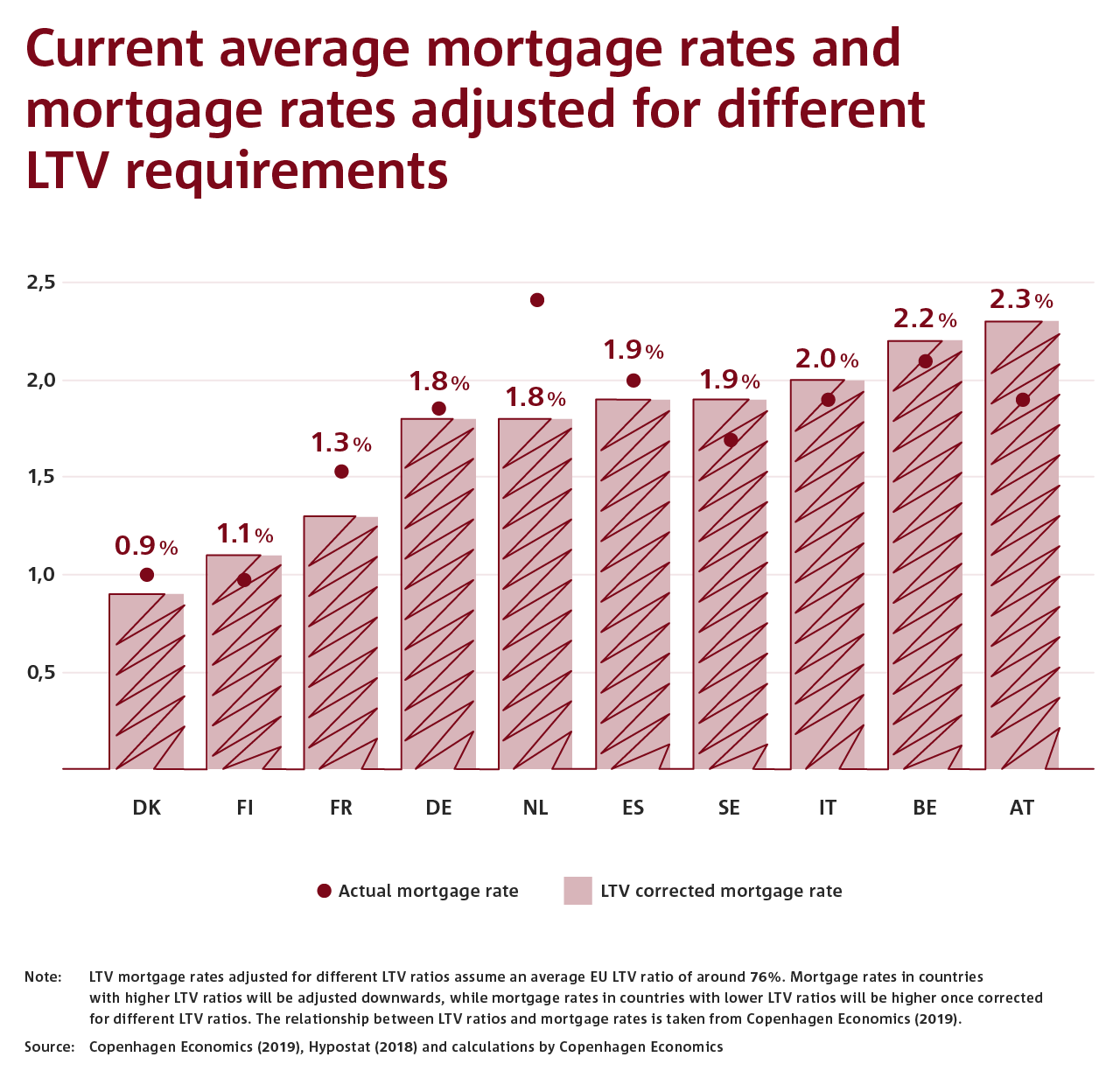

An important case of market fragmentation is mortgage lending, the dominant segment of retail banking services.[11] The lack of integration on this market could in turn hold back integration of other banking services, as the choice of housing loans often leads to cross-selling of other banking products.[12]The difference in the mortgage markets includes the inherent risks for the credit institute, e.g. due to different insolvency laws, as well as different mortgage market structures such as the possibility of mortgage equity withdrawal, refinancing possibilities and the level of development of secondary markets (covered bond and mortgage-backed security markets), cf. Box 1 below.[13]It is important to note that mortgage rates remain substantially diverse even after controlling for national differences in loan-to-value ratios, for instance.[14]This confirms the notion that more structural disparities in mortgage markets across the EU are central to explaining fragmentation of European banking markets.

Box 2 Case: Mortgage loans in Denmark, Germany and Italy

To illustrate the fragmented and structurally different mortgage markets in EU, we have compared the market for mortgage loans in Denmark, Germany and Italy.

In Denmark, mortgage lending is mostly provided by specialised mortgage banks which almost exclusively issue covered bonds to fund the mortgage. Danish mortgage markets are bound by the so-called balance principle, which requires a match between the inflows (borrowers’ payments to mortgage bank) and outflows (mortgage banks’ payment to bond owners) of a mortgage bank, thus eliminating refunding and interest rate risk for the mortgage institute.

In contrast to the Danish market, covered bonds in Germany (Pfandbriefe) are a less common form of financing, with a share in outstanding residential mortgage loans of around 17%. Instead, savings deposits and other bank bonds are important funding instruments for mortgage loans.[15];Thus, there is no 1-to-1 correspondence between the funding instruments and the mortgage loans.

In Italy, complicated insolvency laws and limited possibilities of evictions give rise to larger losses in case of default. Thus, mortgage lending in Italy is a product with a larger risk entailed than for example in Germany and Denmark.

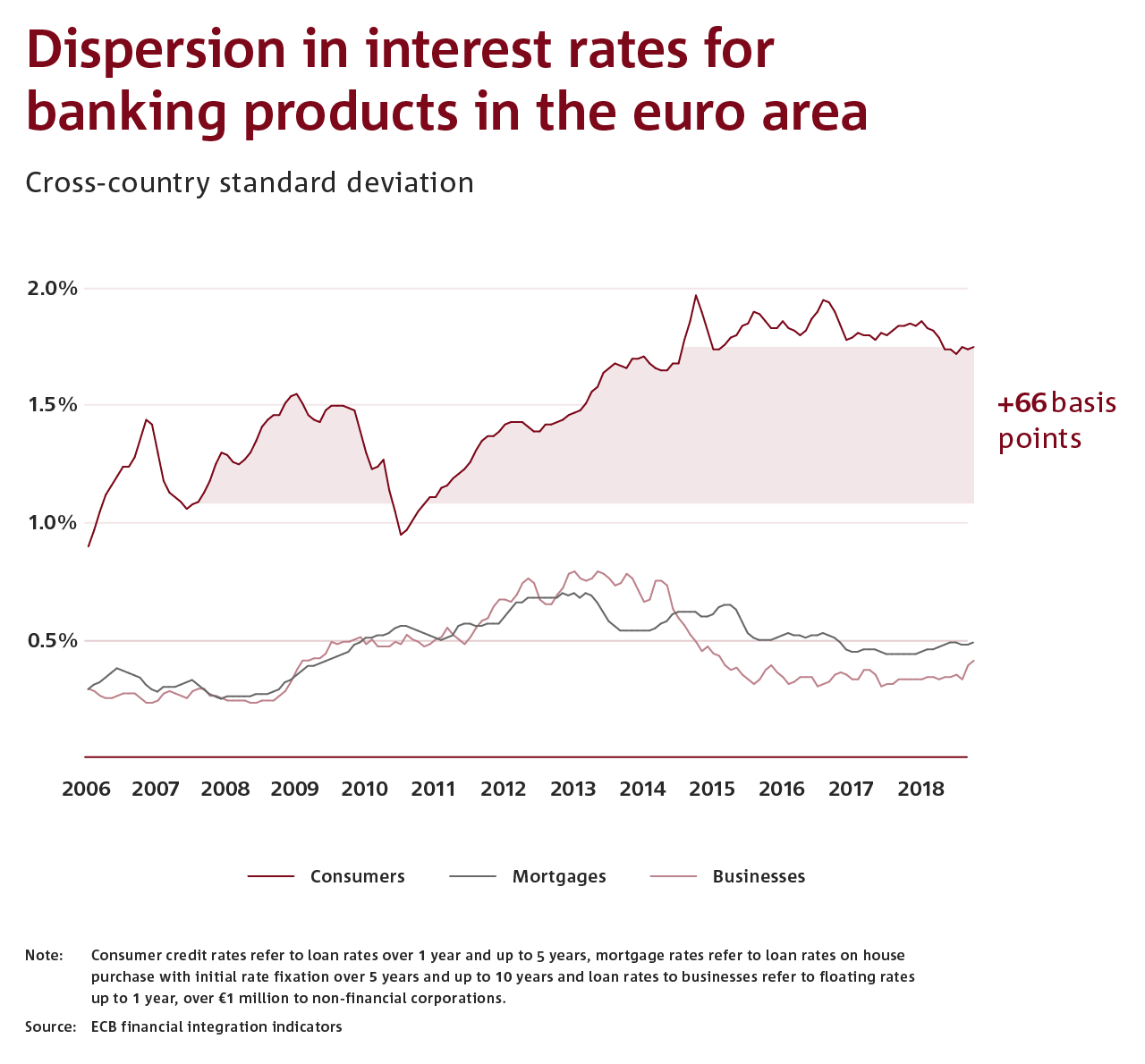

1.3.5 No sign of convergence in interest rate differentials

Looking at interest rate dispersions, there are no signs of increasing integration of the European retail banking market. In a more integrated banking market, banking products could be more similar and thus interest rate dispersion should be lower. But this has not been the case in Europe, where interest rate dispersion has increased since the financial crisis, cf. Figure 5.

1.4 Digitalisation could drive increased cross-border banking

As will be outlined in the next chapter, the fragmented European banking market has, to a large degree, its origin in insufficient political efforts to remove regulatory obstacles to cross-border banking.

Nevertheless – in particular within direct cross-border banking – there is a more straightforward reason for the fragmented banking markets; the need for physical proximity in banking.

- From a consumer perspective, trust plays an important role in banking and trusting a foreign bank and their products is likely a barrier, and the lack of clear information about foreign products has also been an impediment.

- From the banks’ point of view, they might be limited in their risk assessment due to less knowledge of different risk factors in other countries.[16]Additionally banks are hindered by “Know Your Customer”-obligations, which can be a challenge cross-border.

However, in a number of ways, the ongoing digitalisation process of the banking sector could gradually diminish the need of physical proximity:

- New online tools and mobile applications allow customers to manage their banking activities without the need to visit a local bank branch. Customers can thus have digital access to banking products and services from anywhere in the world. This might even increase due to new technologies such as Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) or a possible digital Eu-ro (Central Bank Digital Currency).

- The lack of trust in cross-border banking products can be alleviated by increased transparency through online ratings and exchange of experiences. The possibility of setting up online video calls with personal advisers anywhere can mitigate concerns and provide an alternative to face-to-face advice in the local bank.[17]

- Bank customers can be identified digitally at distance, for example through online video solutions or remote biometric technologies. This makes it easier for banks to comply with the “Know Your Customer” and anti-money-laundering requirements when providing services across borders.

- Finally, general low levels of switching in banking (compared to other sectors) make it difficult to enter a new market. Providing online tools for comparison of financial services makes it easier for customers to find the most fitting banking product for their needs, no matter where a bank is located.[18]Moreover, language barriers that could impede cross-border banking even in a digitalised world can also be expected to become less pressing with the continuous advance of good online translation services.

Studies have shown[19];that many customer groups are still satisfied with the physical connection to their local branch. Thus, we do not expect sweeping conversion in a few years – but a gradual transformation increasing the possibilities for direct cross-border service of customers within banking.

Chapter 2

Benefits of an integrated banking market

In the previous chapter, the current substantial fragmentation of the European banking markets was outlined but also how digitalisation is a great window of opportunity to ignite renewed integration. In this chapter, the attention is turned to the costs of the fragmented banking market – or put differently – what are the potential benefits of a single banking market in the EU?

First, we describe why a single banking market would provide benefits for banks and EU banking customers (section 2.1). Second, these benefits are quantified and concrete estimates are provided (section 2.2).

2.1 Three main benefits of a single EU banking market

An integrated European banking market will have a range of benefits for banks and banking customers, as recognised in numerous studies. For example, the European Commission writes that an integrated European market for retail financial services will “improve choice for consumers, allow successful providers to offer their services throughout the EU, and support new entrants and innovation”.[20]

Concretely, we have identified three main sources of economic benefits from an integrated banking market, which we will go through in the following.

2.1.1 Spread of most successful business models

In an integrated market, banks could supply their products unrestrictedly in all EU countries. This means that the most profitable and cost-efficient banks would be expected to gain market shares in the EU through competition with less efficient banks – either through direct cross-border banking, or indirectly from acquiring (less efficient) domestic banks.

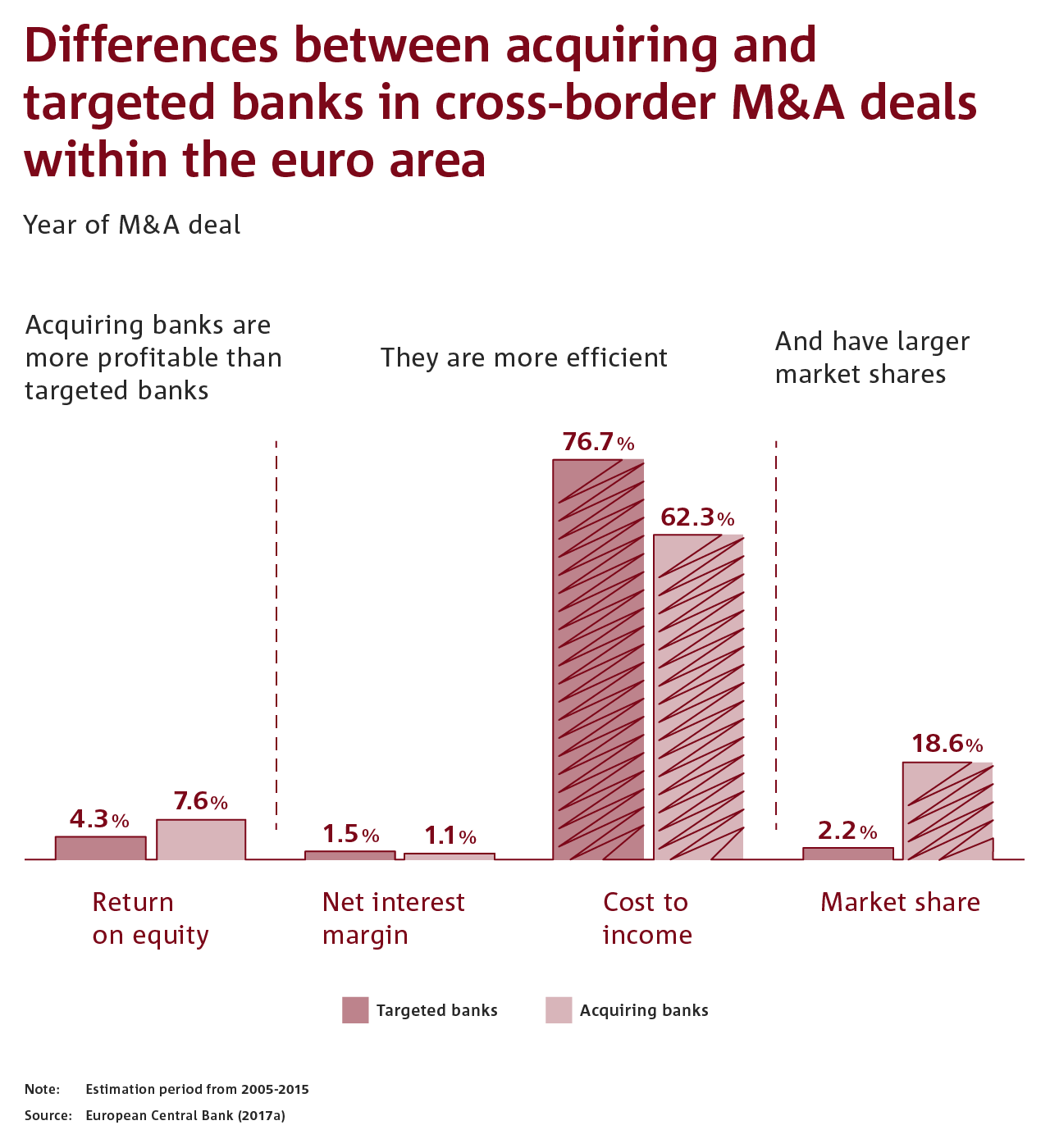

As such, cross-border banking will increase EU banking market efficiency. This is in line with empirical research conducted by the ECB. They find that in cross-border banking M&A deals, more efficient banks typically target weaker banks whose cost-structures they can improve, cf. Figure 6. [21]As a consequence, targeted banks tend to become more profitable and more cost-efficient in the years after the deal, for example, as the targeted bank adopts the more efficient systems and procedures of the acquiring bank.

This notion is also supported by findings that banks in more concentrated markets tend to be more efficient; consolidation improves banking efficiency.[22]

2.1.2 Economies of scale and scope

The increase in market share of the efficient exporting banks and the associated process of consolidation in the European banking market, would – in turn – lead to costs savings due to economies of scale.

The existence of substantial economies of scale in banking is widely recognised in recent empirical research.[23]For instance, one study based on European data finds that on average, a 100% increase in output increases total costs by 86%.[24]

The main driver behind this is that fixed costs becomes more diluted - when the size of the bank increases, i.e. lower fixed costs per-unit output. And the substantial economies of scale effects in banking should be seen in the light of the existence of many large fixed costs, or at least costs that do not increase correspondingly to an increase in output. This includes for example costs related to:[25]

- Regulatory compliance.

- Establishment of IT systems that can deliver banking services to customers.

- Establishing payment systems that allow customers to send and receive payments.

- Risk management schemes that can accurately determine the risk profiles of potential customers.

- Large “IRB-approved” institutions are allowed to use their own risk models to deter-mine their capital requirements. Developing these risk models involves large one-off costs, but then in return often leads to lower capital requirements.

Finally, cross-border banking could drive increased specialisation in certain banking services, supported by the emergence of so-called open banking platforms.[26]This could lead to lower costs for banks due to sales of fewer banking products at a larger volume. When banks specialise in the provision of a certain product, they can do so more efficiently because they can focus all their resources on improving processes for this one product only. For example, a bank focussing on credit provision to SMEs, might have more adequate models for risk-assessment and better inside knowledge of the industry. It could thus build a reputation as credit provider for small companies, giving it a competitive edge over other banks in that segment. While national markets might be too small for such a strategy to be beneficial, an integrated European market implies a much larger customer base, thus rendering specialisation profitable.

Initially, these cost-savings benefit the banking sector. This could strengthen European banks ability to keep sufficient credit flow to companies and households affected by the COVID-19 crisis. However, in time, looking past the current crisis, we expect the gains largely to be passed on to consumers as EU-wide competition would drive down banks’ mark-ups, prompting them to lower prices for their customers. Note, that this will not necessarily lead to less suppliers of banking products within each country. Through more effective competition across borders the most innovative and efficient players grow in relative importance. Even though this leads to cross-EU consolidation, the number of firms de facto in play as potential suppliers for consumers may well increase.

This process would also make European banks more competitive globally, opening up markets outside Europe. This is well in line with the German Presidency’s focus on strengthening innovation and digitalisation to allow Europe to exercise its interest and responsibility globally.

2.1.3 More efficient cross-border flow of capital

Finally, an integrated European banking market would imply a better allocation of capital – as capital flows will not be hindered by country-borders. The associated benefits have three dimensions:

Investor perspective: Large cross-border banks with market shares in many different countries provide good diversification of risks for bank equity holders and creditors, leading to less volatile returns, i.e. initially investors in banks will get a higher risk-adjusted return. The other side of this is lower cost of capital for banks going forward, which we expect to eventually be passed on to customers in terms of lower interest rates.

Company perspective: Capital would to a larger degree reach those with the best use of it. As such, availability of credit will be less linked to the functioning of the domestic banking market. For example, structural issues in the banking sector in a given country would imply difficulties for companies in the country to finance new investments. In an integrated European banking market, companies would be able to obtain credit from banks in other countries not affected by the issues, thus alleviating the negative consequences for businesses, investments and economic growth.

Financial stability perspective: First, an increase in banking profitability due to economies of scale and efficiency gains from cross-border banking have a positive effect on financial stability, simply because more profitable banks are less likely to get into financial distress. In addition, capital inflows by foreign banks would stabilise the domestic economy in times of financial distress because foreign banks would be less susceptible to domestic shocks.[27]As such, the negative feedback loop between the real economy and the banking sector would be diminished, thus stabilising the host country’s economy in a period of financial distress.[28] Similarly, domestic banks investing abroad will have a better diversified portfolio, making them less susceptible to domestic shocks.

One aspect of this goes in the other direction in terms of financial stability; strong reliance on funding from foreign banks entails contagion risks if these banks face difficult situations in their home market. Especially since banks tend to discard foreign assets first when facing distress. Nevertheless, economic research in general finds that the benefits from cross-border banking for financial stability outweigh the disadvantages. Studies particularly emphasize the positive impact of better risk diversification on financial stability, as well as the associated enhanced risk-sharing capacities of a fully integrated financial market.[29]

2.2 Estimates of the benefits from a single European banking market

Above the main benefits of a single banking market were outlined.To illustrate these benefits, in this section the benefits from the first two points mentioned in the section above are estimated: Spread of most successful business models and cost-savings related to economies of scale in banking.

2.2.1 Spread of the most successful business models

As described in the previous section, an integrated banking market would lead to the spread of the most successful banking business models through an EU-wide consolidation of the banking sector. This implies that the interest rates within each country, for each product category, will converge towards the “best-in-class” in Europe.

For example, in an integrated market, a country with an inefficient mortgage market and associated high mortgage rates will face competition from foreign banks that are better at providing mortgage loans. This could be because such banks come from countries where mortgage markets are larger and that are thus more specialised in providing such loans at lower costs, due to more efficient risk management or a better structure of funding the mortgage loans.

Furthermore, it may also reflect wider framework conditions that impact expected losses and agency costs associated with providing and monitoring loans. We will discuss this later but, clearly, divergent rules regarding foreclosures, default regimes etc. have a manifest effect on differences in lending rates across the EU. Rules put in place to protecting defaulting borrowers will ultimately be paid up front by borrowers via a high interest margin, particularly borrowers with high default risks.

To illustrate the benefits, Copenhagen Economics has estimated the potential benefits of converging interest rate margins in the EU banking markets. In the estimation, it was assumed that the interest rate margins (the difference between loan and funding rates as a share of financial assets) will converge downward until the variance across the EU is on level with the average variance in those countries with the most integrated banking markets in the EU (see appendix for a detailed description of the estimation).[30]

Copenhagen Economics finds that this could lead to annual costs savings in interest expenditures of around EUR 60 bn in the EU-27 (excluding UK), corresponding to around ½ percent of total EU-27 GDP.[31]

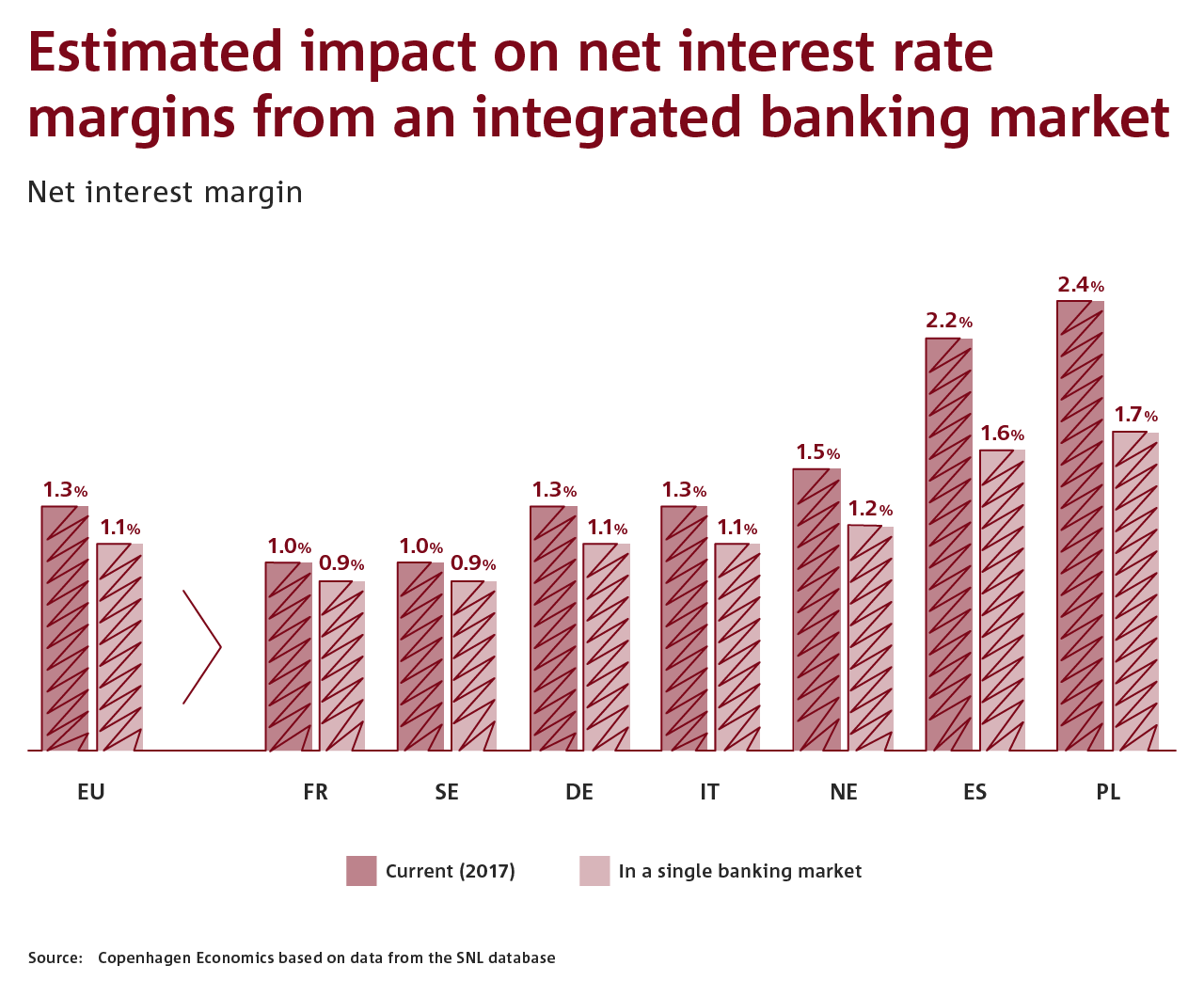

The costs savings in annual interest rate expenditures correspond to a decline in the average interest rate margin in the EU of around 0.2 percentage points, cf. Figure 7.

We expect the impact of a single banking market to differ in magnitude in the different countries, with the largest effects in countries which currently have the largest net interest margins cf. Figure 7. In these countries there are larger differences in profitability and efficiency of banks, implying more potential in terms of efficiency improvements in M&A targeted banks or from direct cross-border banking.

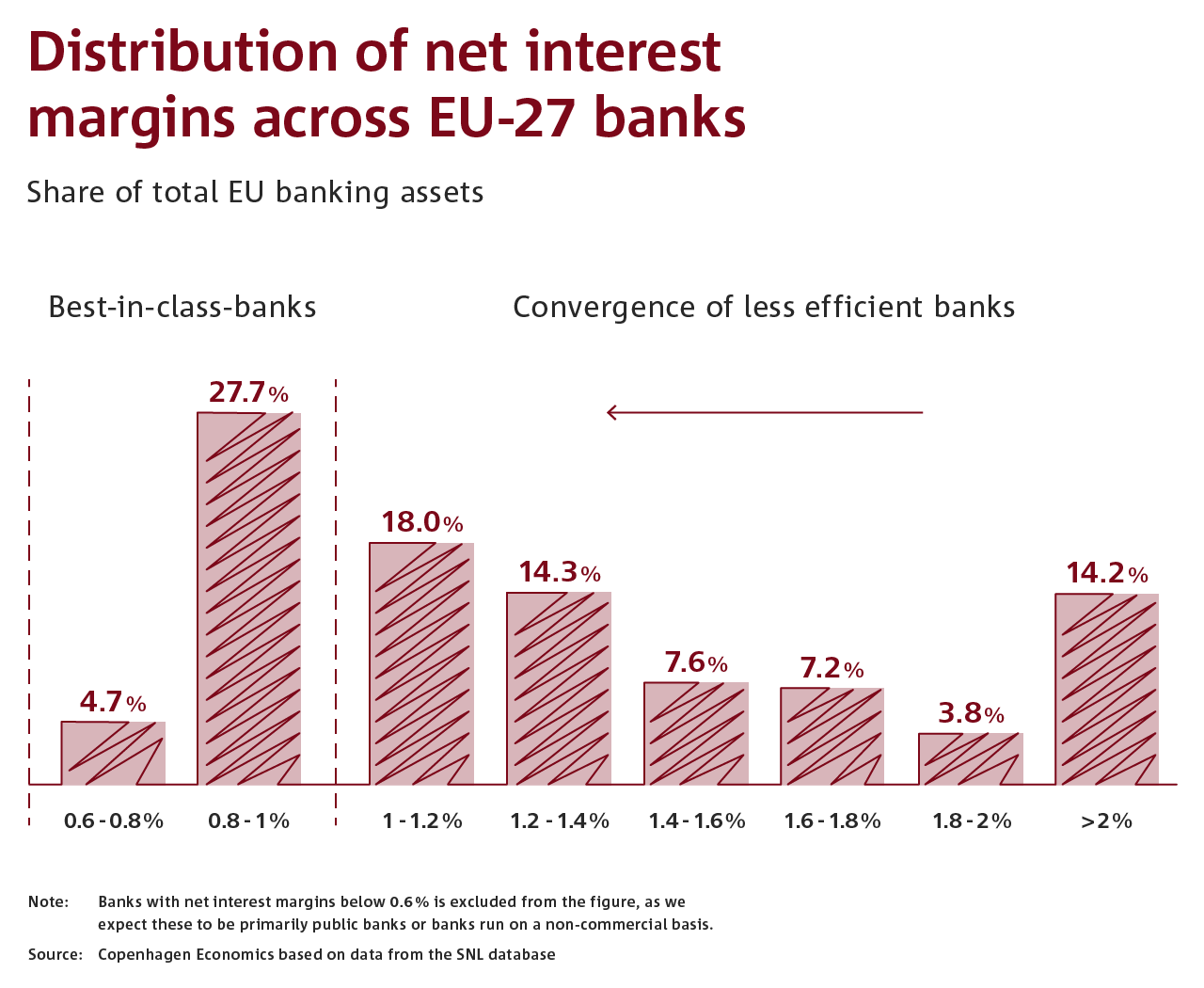

Looking across the EU banking sector, the current distribution of net interest margins are rather dispersed, cf. Figure 8. While the largest group of banks have net interest margins between 0.8% and 1%, a considerable number of banks have much larger net interest margins. For instance, more than 30% of banks have interest rate margins above 1.4%. Convergence of net interest margins to the best-in-class due to the mechanisms described above would imply a move to the left of this distribution with banks becoming more efficient, cf. Figure 8.

Finally, we also expect that an integrated banking market will lead to lower differences in interest rates within each country, as it is primarily high-cost banks in each country that will be the target of foreign competition. The within country interest rate differentials are currently quite substantial in some countries, cf. Figure A.1 in the appendix.

2.2.2 Increased economies of scale

As described above, efficient banks will gain market shares in an integrated European banking market. This means they will become bigger and thus be able to benefit from economies of scale, leading to further cost savings.

We suggest that this is an additional benefit to the EUR 60 bn above. To estimate the economies of scale, Copenhagen Economics looked to the market shares of the largest American banks. Although there are many differences between the European and American banking markets, they are on a high-level similar in size and fundamental economic and financial structures, e.g. they both have market economies, following international Basel standards.

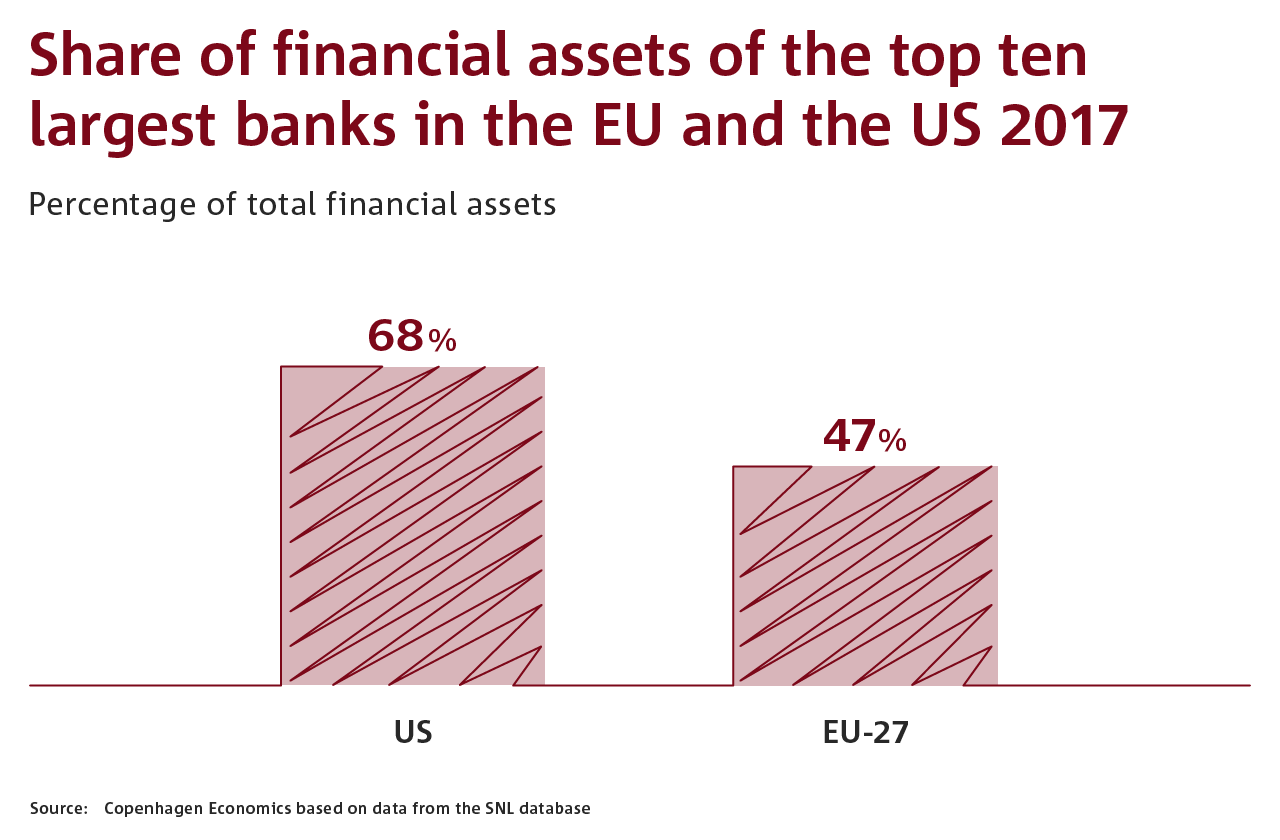

However, the U.S. banking market is much more deeply integrated than its European counterpart and banking assets are considerably more concentrated in the U.S. For example, the ten largest banks in the U.S. account for around 68% of total financial assets compared to 47% in the EU, cf. Figure 9.

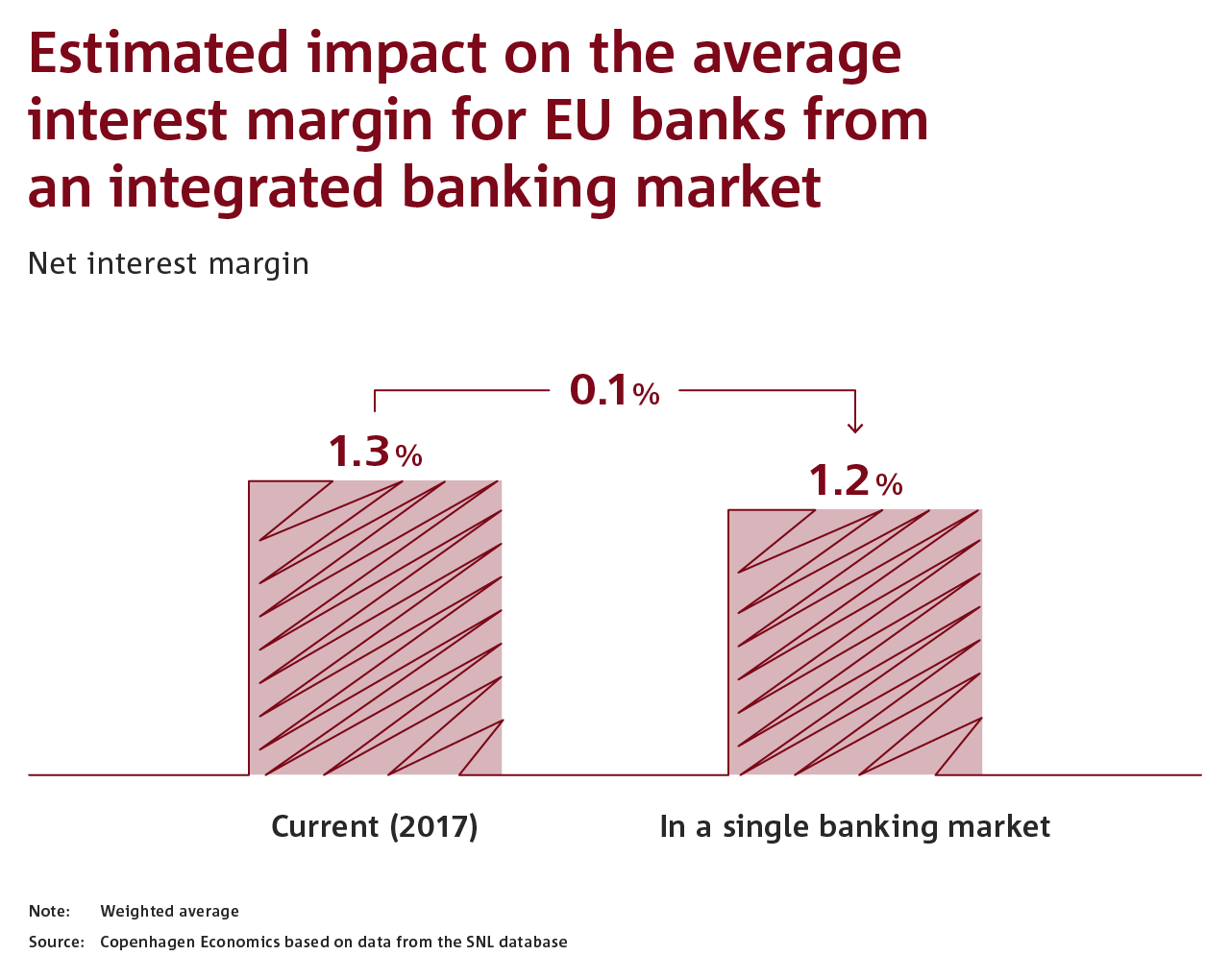

To estimate the cost savings for European banks resulting from economies of scale, it is assumed that banks’ market shares in the EU will mimic those in the integrated U.S. banking market. As mentioned above, a study suggested that, when production in a given institution expands by 100%, costs increase by only 86%.[32] This would result in total cost-savings of around EUR 35 bn for the largest European banks, corresponding to slightly more than ¼ percent of EU-27 GDP.[33]This would imply a reduction in the average net interest margin of EU banks of around 0.1 percentage points, cf.Figure 10.

Adding the benefits from downward convergence of interest rates and economies of scale effects, the total potential cost savings from an integrated European banking market amounts to close to EUR 95 bn corresponding to around ¾ percent of EU GDP.

Chapter 3

Barriers to an integrated European banking market

Having estimated the potential benefits from a single market within banking services, we now turn our attention to analysing the barriers preventing it. Removing the barriers to a single banking market, as described above could eventually lead to potential efficiency gains of close to EUR 95 bn.

In this chapter, we first outline four types of barriers that should be eliminated if European banks and customers are to be able to reap the full benefits of a single banking market (section 3.1). We then suggest four packages of regulatory initiatives that will help the EU deliver on some of that potential (section 3.2) and explain how they would work in bringing about the total estimated efficiency gains.

3.1 Barriers to an integrated European banking market

From a high-level perspective, the reason for the currently fragmented EU banking markets is in fact quite straightforward; supplying banking services cross-border is not a profitable business case for EU banks. This makes the solution to the problem equally simple; the business case of supplying products across EU borders has to be made profitable.

To achieve this, we have identified four main barriers that currently make cross-border banking unprofitable for European banks, which we will go through in the following, cf. Figure 11.

3.1.1 Barrier 1: Legislation posing a direct cost to cross-border banking

First, a range of factors in the current regulatory setup, that give rise to direct costs in conducting cross-border banking were identified:

- Capital and liquidity requirements punish cross-border banking: Banks have to be compliant with capital and liquidity requirements within each entity of a cross-border group, even if the subsidiary is located in a member country of the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM). This ring-fencing ties up capital, thus making cross-border banking costlier.[34]

- Calculation of the G-SIB surcharge discourages cross-border banking in the EU: Banks deemed as globally systematically important banks (G-SIBs) are required to hold additional capital depending on how systematically important they are. When calculating the size of these G-SIB capital buffers, cross-border exposures are among the indicators that define the size of the additional capital buffer. However, the SSM is not treated as a single jurisdiction when calculating G-SIB buffers and intra-EU financial flows are thus defined as cross-border exposure. This makes banking activity in other EU countries more expensive than domestic banking and might lead to higher capital requirements for large cross-border banks in Europe, compared to cross-state banks in the US, for instance.[35]

- Cumbersome cross-border banking reporting requirements: Different reporting requirements across countries increase the compliance costs of providing cross-border services.

- Compliance-heavy M&A process: M&As entail high compliance costs in general, but especially so if conducted across borders. This is mainly due to differences in national laws that govern mergers. Moreover, national supervisory authorities in the country of the targeted bank have to approve the transaction in several EU Member States.[36] This can be problematic if regulation is used to fend off foreign entry, as has been the case in some instances in the past.[37]In particular, there could be an interest in defending so-called national heroes”, e.g. banks which are among the biggest in the given country, which authorities would like to keep in domestic hands. The need for transparent M&A processes has also been acknowledge recently by the ECB.[38]

3.1.2 Barrier 2: Legislation providing an unlevel competitive playing field across borders

Different regulations and tax systems lead to an unlevel playing field for financial institutions operating in countries with more stringent rules or a higher tax burden. For instance, additional taxation on financial institutions’ profits and remunerations in some EU countries or higher capital requirements (e.g. additional countercyclical capital buffers in France or Germany before the pandemic) increase the costs for banks at the group level. If these costs are too substantial, it might prevent some banks from competing with banks located in countries without such levies.

Concretely, there are mainly three factors giving rise to unlevel playing field across borders:

- National gold-plating: This implies that rules are implemented in a more profound manner than outlined in the EU directive. The frequent use of directives instead of regulations as well as the persistence of options and discretions (O&Ds) make such a divergence possible. This leads to cross-country differences in regulations, disadvantaging institutions located in countries that engage in gold-plating. Especially direct cross-border banking and the establishment of cross-border branches are affected by this, because these have to comply with requirements in their home country. However, subsidiaries are also impacted because capital and liquidity requirements have to be fulfilled also at the group level. So even if a subsidiary is established in a country with more lenient regulation, it is still affected by the requirements the parent company faces in the home country.

- Taxation of the financial sector: Different tax systems can give rise to competitive disadvantages for affected banks. In France, for instance, an additional wage tax on financial sector labour input implies relatively higher costs for French banks compared to countries where such a tax is not levied. This adversely affects direct exports by French banks as well as the services provided by subsidiaries located in other countries since back-office services in the parent company are more expensive. For the same reason it also discriminates against French banks compared to foreign competitors in France because these can rely on services from the parent company back home which are produced without taxes on labour costs. Some countries also have elevated corporate taxation, which give rise to similar issues.

- Different VAT levels: Different VAT rates across countries also affect the competitive position of banks. Most banking services are not VAT liable in the EU. This means that banks cannot deduct the VAT they pay on their inputs. This leads to so-called irrecoverable VAT payments, which increases the price of banking products. In countries where the VAT rate is lower, such irrecoverable VAT payments are lower as well, thus making those banks more competitive compared to banks located in countries with high VAT rates.

3.1.3 Barrier 3: Barriers to digitalisation of the banking sector

As described above, digitalisation could by itself be a catalyst for increased cross-border banking. However, the digitalisation process in the banking sector is limited by:

- Different know-your-customer (KYC) rules: Cross-border border banking – in particular direct – is currently limited by different KYC rules and standards in each country. Digitalisation of the KYC process will make identification of customers at distance possible (see chapter 1). However different national KYC rules make serving markets in other EU countries more costly for banks and effectively render direct cross-border banking impracticable if European customers do not have at their disposal identification documents required in another EU country.

- Some “analogue requirements” remain and differ across countries: In Germany, for instance, it is still a requirement to accept a customer loan by paper signature or “qualified electronic signature”, which requires certain infrastructure. Such national rules limit the potential of digitalisation in banking.

- Outsourcing rules: Outsourcing rules and definitions are not fully harmonised across EU countries and the application of existing harmonized rules seem to differ across member states. This relates, for instance, to the possibility of using foreign cloud services in banking. This is especially relevant in the context of creating a digital European banking market as harmonized outsourcing rules are necessary for promoting open banking, cooperation with fintechs.

- Non-harmonised regulation of crypto assets: Provides uncertainty regarding the legal framework. This could hamper crypto assets distribution across the EU, not allowing businesses and households to reap the full benefits of the technology. In addition, the incoherent legal framework prevents sufficient scale in developing new crypto asset solutions for innovators.

3.1.4 Barrier 4: The design and properties of products sold in each country are different

The design and properties of banking products differ between countries in the EU. And when banks supply financial services cross-border, they have to be adapted to these country-specific conditions. This implies that banks cannot simply resell their products, posing limitations on the beneficial effects of economies of scale in banking. Two main reasons for this:

- Differences in private law: Consumer protection rules, insolvency laws and company law differ across EU countries. This implies that banks have to comply with national regulation and legislation when exporting their products and adapt to changes in legislation on a national level in each country where they are present. This is costly and hinders cross-border banking, making the business case for cross-border banking less profitable. For instance, banks supplying mortgage loans in different countries would have to take into account varying collateral requirements, different national property rights as well as compulsory sale procedures.

- Different economic and financial structures: Product design is also influenced by cultural differences and customary habits, which are, in turn, influenced by legislation and regulation. The prevalence of fixed instead of variable rates for mortgage loans in countries like Germany and France and different standard maturities of mortgages are examples for this.

3.2 Four packages of initiatives to remove the four barriers

Concretely, we suggest four regulatory packages, grouped by the barrier they primarily address. This division of initiatives is not definitive, and we would expect some of the initiatives to work on several barriers.

3.2.1 Streamlining legislation making cross-border banking less costly

Currently, there are a range of additional costs for European banking associated with expanding cross-border banking, compared to domestic expansion. These relate to indirect cross-border banking, primarily through M&A deals, as well as direct cross-border banking. An obvious step to make the business case for cross-border banking for European banks more attractive would be to directly target the associated costs. Concretely, we suggest to:

Harmonise the legal and regulatory basis for M&A transactions: This includes limiting the influence of national regulatory bodies, that could have an interest in protecting “national heroes”. A higher prevalence of such cross-border M&As in the EU would be an important boost in bringing about the associated efficiency gains for banks and lower costs for banking customers that a true single banking market entails. In particular since the majority of cross-border expansions are conducted through M&A as described in section 1.3.

Allow capital and liquidity waivers such that associated regulatory requirements can be complied with at the group level only: This would enable banks to allocate their capital more efficiently within the banking group, thus preventing capital and liquidity being tied up within a groups’ foreign subsidiaries. Copenhagen Economics expects that this could unlock up to EUR 100 bn CET1 capital at European banks – which in turn could be used to support credit provision.

Banks operating in other countries through branches can already circumvent additional costs generated by capital and liquidity requirements in the host states. Introducing capital and liquidity waivers would thus make the establishment of a subsidiary in a foreign country more attractive. This is also relevant for countries outside the Euro Area, wanting to expand within the Euro Area, as this requires the establishment of a subsidiary in a Euro Area country.[39]

Streamline cross-border banking reporting requirements: This will directly reduce the additional compliance costs currently related to cross-border activities. The increase in bank data requirements over the past years suggests that this harmonization of reporting requirements has the potential to significantly reduce costs for banks. Streamlining the reporting process and establishing a common definition of data requirements would therefore make cross-border banking less cumbersome. We welcome the mandate given to the EBA to analyse the development of a consistent and integrated system for collecting statistical data.[40]

Allow cross-border exposure within the SSM to be treated as domestic exposure for the calculation of Basel surcharges: This is a good example of how regulatory authorities treat cross-border banking differently to domestic exposure even if transactions are realized within the SSM. To create a truly integrated European banking market, costs related to cross-border banking within the EU, such as a higher G-SIB surcharge, should be eliminated.

3.2.2 Providing a level playing field between banks in the EU

Regulatory divergence and differences in the taxation of financial institutions can give rise to an unlevel playing field and hamper the creation of an integrated European banking market. Harmonisation of national approaches should therefore be advanced as far as possible. This translates into two broad initiatives:

Remove the possibilities for national gold-plating: Reducing the instances of gold-plating would imply that foreign and domestic banks can compete on more equal terms. This could be achieved by making less frequent use of directives — where national authorities have more discretion when transforming directives into national law and by harmonizing existing national options and discretions.

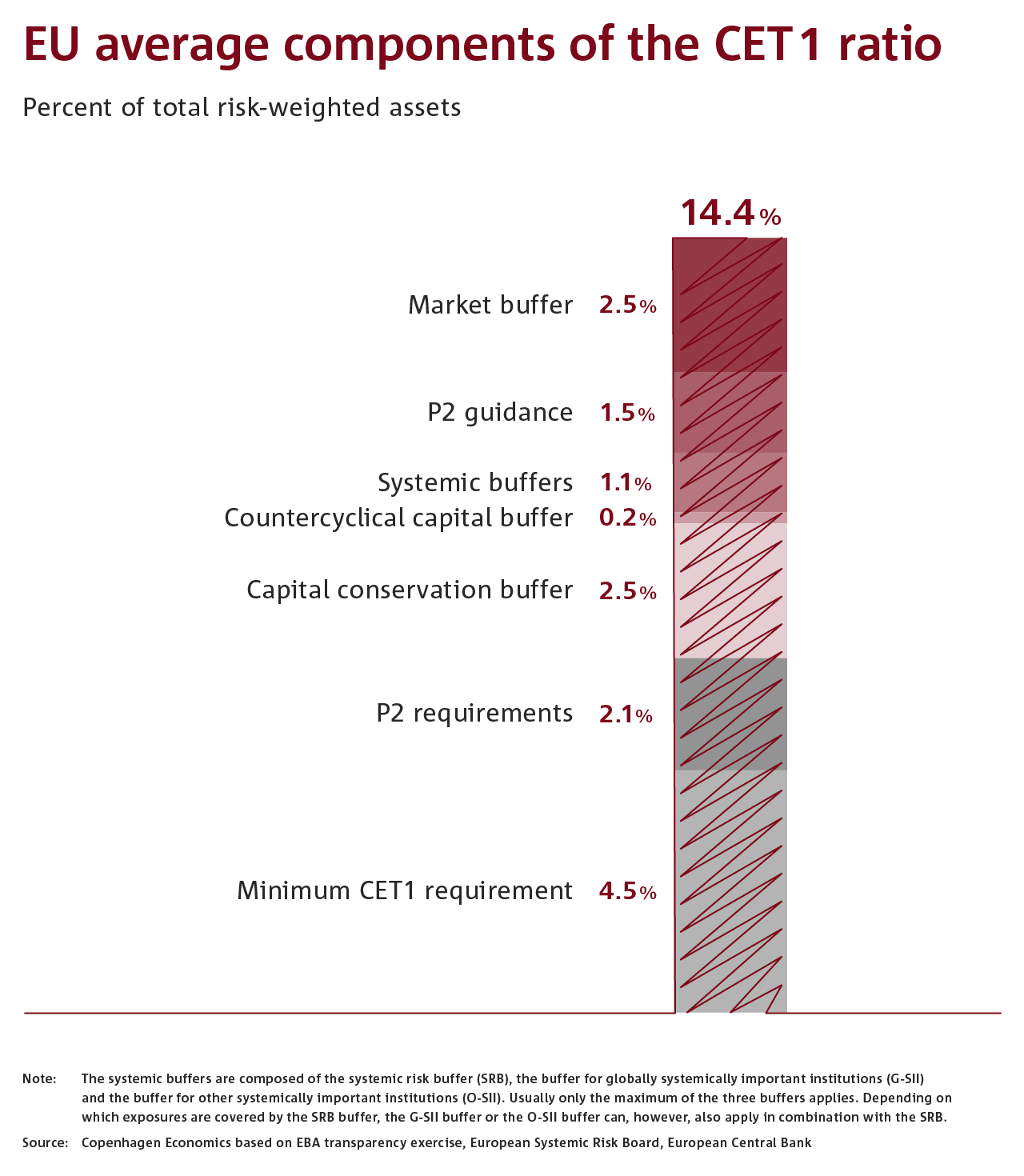

Currently, banks from countries with a regulatory framework that is stricter than stipulated by EU law have a competitive disadvantage when serving customers in countries where rules don’t exceed European requirements. For example, capital requirements are composed of different parts (cf. Figure 12), some of which are subject to a substantial degree of national discretion, in particular the buffer for other systemically important institutions (O-SIIB), the systemic risk buffer (SRB), Pillar 2 requirements (P2R) and Pillar 2 guidance (P2G). It is very difficult determine how much of the difference in EU capital requirements is a result of different regulatory approaches, but recent evidence suggest this is substantial.[41]

Concretely, Copenhagen Economics estimates that reducing national gold-plating with respect to capital requirements could free up (CET1) capital in the magnitude of EUR 100-140 bn for European banks, corresponding to a reduction in the average CET1 ratio of around 1.3-1.8 percentage points.[42]This would reduce funding costs for European banks, as capital is a much more expensive form of funding than debt financing. Concretely, Copenhagen Economics estimates it could lead to total annual cost savings for European banks of EUR 11-16 bn.[43] If passed on to customers, this could on average lead to a reduction in the price of financial services of 1.6%-2.3%. These are average figures. However, the cost savings would primarily be realised in banks subject to heavy gold-plating, thus contributing to bringing about a more level playing field.

Align taxation of financial institutions: Similar to the dynamics described above, banks located in countries with higher tax rates or more comprehensive tax systems have a competitive disadvantage when competing abroad. Aligning tax rates would therefore make for a more level playing field and support competition in the European banking market.

To illustrate this point, Copenhagen Economics has estimated the difference in the cost of banking with corporate tax rates of 30% and 25% (e.g. the difference between the corporate tax rate in Germany and the Netherlands), using a simple cost-of-capital calculation. The higher tax rate creates a wedge between the (before-tax) required return on equity, which gives rise to higher funding costs.[44]Concretely, Copenhagen Economics estimates that funding costs are around 5 basis points higher (a price increase of 3%) as a result of the higher tax rate.[45]

3.2.3 Removing barriers to digitalisation of the banking sector

In order to utilize the potential of digitalisation for cross-border banking, different KYC rules and verification processes should be harmonised across the EU, at best paving the way for digital identification of customers. Thus, we propose to:

- Align and remove analogue requirements to accessing banking products and harmonise KYC-rules: Removing analogue requirements and harmonising KYC rules means that cross-border banking becomes less costly because banks do not have to comply with different rules in different countries anymore. With the advance of digitalisation, the harmonisation of these rules would most likely further promote cross-border banking as geographical distance becomes less important and European KYC rules could, for instance, be fulfilled online.

- Harmonising outsourcing rules: Common rules for outsourcing would reduce the compliance costs for banks when serving customers in different countries. Enabling banks to make better use of outsourcing is also important to promote open banking and digitalisation in general, thus fostering competition in the European banking market.

3.2.4 Harmonising the nature of products sold in each country

The perhaps most important objective is to open up the possibility for banks to provide the same product in different countries, thus allowing them to reap the benefits of economies of scale. Note that this objective is not to restrict the current offering of product, but to increase the product offering through cross-border supply from banks in other countries.

While this objective would mean a large step towards a deeper integration of the European banking market, it will often entail harmonisation or reforms of national private law, which can be a major challenge; some of the laws are deeply enrooted in the countries’ legislation and affect other sectors than just banking. Therefore, we expect progress within this initiative to be rather slow. Concretely, we suggest to:

- Harmonise insolvency laws: Currently, differences in, for instance, property rights and foreclosure procedures mean that banks operating in foreign countries are forced to make individual risk assessments for each country when supplying banking products. This implies that they cannot resell the same product in different European countries, which increases the costs of cross-border banking. With aligned insolvency regulation, banks could more easily compete with their banking products in other European countries. In doing so, one could look to countries with currently well-functioning insolvency laws to establish best practice. The harmonisation has become even more relevant in the face of the COVID-19 crisis, which could have compounded costs of solvency laws that provides costly and lengthy procedures to deal with defaults. As such, banks could retract even more from providing necessarily lending as the pandemic is increasing the financial risks of defaults. Thus, we suggest that the recovery programmes put in place by national governments addresses these factors to maximise the contribution that the banking sector can deliver in putting the EU economy back on track.

- Harmonise consumer protection rules: Similar to above, harmonised consumer protection rules would enable banks to sell the same product in different countries, thus allowing them to fully reap the benefits of economies of scale. Cross-border banking would be more attractive if banks did not have to comply with various different consumer protection rules.

- Harmonise mortgage regulation: Currently, national rules regarding the registration of collateral as well as different country-specific rules, e.g. on how collateral can be used when calculating banks’ regulatory capital, force banks to comply with different regulatory frameworks when supplying mortgages in countries other than their home country. Harmonising such national requirements would make it easier for banks to sell one product across European borders. Again, such harmonisation could benefit from taking into account existing national systems that have proven to be efficient, especially in regard to requirements for collateral.

To illustrate the potential impact of the harmonisation of insolvency laws and mortgage regulation in Europe, Copenhagen Economics has estimated the impact of converging mortgage rates to the lowest rates in Europe.[46]These mortgage rates are corrected for the influence of different national loan-to-value (LTV) ratios on the mortgage rate (cf. Figure 13).[47]As before, the rationale behind this convergence is that with aligned regulation, banks with the best and cheapest mortgage products could offer these products within the entire EU, thereby increasing competition and lowering prices. Copenhagen Economics estimates that this convergence could imply cost savings of close to EUR 30 bn per year in the entire banking sector, corresponding to around 0.2% of EU-27 GDP. Thus making a significant contribution towards realising the total gain of EUR 60 bn from converging interest rates in the EU. On top of this, would come cost savings in terms of higher economies of scale.

[1] See European Council conclusions 2020, paragraph A18 and A19.

[2] European Commission (2018)

[3] European Commission (2015a)

[4] European Commission (2015a), Bertelsmann Stiftung (2018)

[5] European Commission (2016a), p. 22 and 23, for instance.

[6] Moreover, the decision of whether to open a branch or subsidiary can also have implications for the amount of taxes to be paid and for the treatment of profits in general, see International Monetary Fund (2011).

[7] Schmitz & Tirpák (2017), Bremus & Fratzscher (2014) and Deloitte (2012)

[8] ECB (2012) - Special feature A; Giannetti et al. (2012)

[9] European Central Bank (2017a)

[10] In the next chapter, we present four main barriers to cross-border banking, where “nature of product sold in each country differ” is one of them

[11] Bouyon (2017)

[12] Copenhagen Economics (2018a)

[13] International Monetary Fund (2008), Ch. 3

[14] Copenhagen Economics (2018a); see also Figure 13 below.

[15] International Monetary Fund (2008), ch. 3, European Covered Bond Council (2018) and Hypostat (2018)

[16] Known as the “church tower principle”

[17] European Commission (2016b)

[18] European Commission (2016b)

[19] E.g. FED (2018), who argue that small and local businesses, as well as customers aged 45 and up still have significant preference for physical bank branches.

[20] European Commission (2015b)

[21] European Central Bank (2017a)

[22] Deloitte (2018)

[23] See for example, Beccalli et al. (2015), Dijkstra (2013) for Europe and Wheelock et al. (2009). Feng et al. (2010) and Hughes et al. (2013) for the US.

[24] Beccalli et al. (2015)

[25] See e.g. FSA and BoE (2013)

[26] See Copenhagen Economics (2019): How digitalisation is changing the competitive dynamics in banking

[27] Allen (2011)

[28] Financial distress typically leads to less lending to the real economy, which might increase the likelihood of defaults of domestic businesses. This, in turn, worsens the position of domestic banks, which then provide even fewer loans.

[29] Schmitz et al. (2017) and Allen (2011)

[30] Copenhagen Economics assumed that the convergence of net interest margins continues until the variation in banks’ net interest margins across EU countries reaches the average value of the ten countries with the most integrated banking markets (lowest within-country standard deviation). These countries are: Sweden, the Netherlands, France, Romania, Finland, Malta, Luxembourg, Italy, the Czech Republic and Denmark.

[31] This result is of similar magnitude as in Dunne (2014), that finds that interest rate savings due to a fully integrated EU-wide financial services sector could be in the order of 60 bn per year. They find that in an integrated banking market, efficiency gains could be as large as EUR 60 bn per year due to lower mortgage rates and other bank lending rates. In their estimation, they broadly adjust for some constraints to cross-border banking that are expected to persist even in an integrated market (e.g. language barriers)

[32] Beccalli et al. (2015) find that economies of scale are prevalent in European banking. Using a dataset of European banks on the STOXX 600 spanning the years from 2000 until 2011, they find an average elasticity of 0.86, implying that a 100% increase in output increases costs only by 86%.

[33] In addition, Copenhagen Economics assumed that banks will gain market share through consolidation only and not through a mere redistribution of banking assets, i.e. the same amount of banking assets will be held by fewer banks.

[34] Enria (2018), ECB (2018)

[35] Oliver Wyman (2017) and ECB (2017a)

[36] See, for instance ECB (2017a) – Special feature “Cross-border bank consolidation in the euro area”.

[37] IMaudos et al. (2019)

[38] See ECB (2020): Clarifying the ECB’s supervisory approach to consolidation

[39] Apart from that, there is evidence that lending through local affiliates is more stable in times of crises than direct cross-border lending through branches, for instance (Allen et al. (2011)).

[40] See Article 430c of the Capital Requirements Regulation II (CRR II).

[41] Recent findings show that Pillar 2 requirements and Pillar 2 guidance are still heterogenous across European countries and that convergence of the methodologies to determine the size of the requirements is not concluded (see, EBA (2017) – Report on Convergence of Supervisory Practices). Moreover, O-SII buffers are not always consistent with O-SII scores which implies that national authorities make use of their latitude when setting the buffer (see ESRB (2018a)). For setting the systemic risk buffers, no objective criteria (such as size of the bank or its cross-border activity) are defined for determining the respective level of the SRB (see ESRB (2018b)).

[42] As an upper bound estimate, Copenhagen Economics assumed that the average Pillar 2 requirements and Pillar 2 guidance would be half the size of what they are currently and that the SRB is never larger than the O-SIIB (if both buffers exist). With these assumptions, the capital ratio would be around 1.8 percentage points lower.

[43] This calculation assumes a before-tax required return on equity of 13% and an EU debt funding rate of 1.3%.

[44] For this calculation Copenhagen Economics assumed a (after-tax) required return on equity of 10% which is in line with the findings of a recent study on the European banking market (see zeb (2018)).

[45] In this estimation, Copenhagen Economics abstracted from other taxes than the corporate tax that affect banks and assume that German and Dutch banks only differ in terms of the required (before-tax) return on equity, but other than that have the same funding structure and debt costs as the EU average.

[46] In particular, Copenhagen Economics assumed that the mortgage rates in all countries converge to the last country which is within the group of countries with the lowest 25% (by banking assets) mortgage rates. This country in the sample is France, so mortgage rates will converge to the French LTV corrected mortgage rate of around 1.3%.

[47] See Copenhagen Economics (2019) for a description of the relation between the LTV ratio and mortgage rates.