Position paper of the Association of German Banks on the issue of open finance

Contents

4. Relevance for the financial industry

b Promoting green finance/supporting sustainable customer behaviour

c) Holistic financial and investment advice

d) New financing and platform services

e) Targeted contextual marketing

5.1 Facilitate a cross-sector exchange of data

a) Data exchange framework for personal and non-personal data

5.2 Technical prerequisites for exchanging data

5.3 Accompanying standardisation and collaboration platforms for the cross-sector exchange of data

1. Executive summary

Nothing works without data: they are at the heart of value creation in a digital economy and now more than ever a strategic production and competitive factor that is decisive to a company’s economic success. The availability of big data is also indispensable for the use of artificial intelligence and machine learning – both future technologies of critical importance and both technologies where the US and China have a clear head start in development and deployment. Access to data and the ability to reuse them are therefore rightly seen as key prerequisites for the technology leadership of tomorrow and for a competitive EU data economy that will strengthen Europe’s digital sovereignty and benefit both consumers and businesses throughout Europe.

When it comes to data-driven innovation, it is becoming increasingly important for companies not only to use data they have generated themselves or to exchange data within a certain industry but also to better understand and satisfy customer needs with the help of data from very different areas of application. For many reasons, however, this still poses practical difficulties for banks and other businesses. These reasons include a lack of access to data outside a firm’s own business or lack of knowledge thereof, heterogeneous data formats, non-existent technical interfaces and uncertainty about the legal framework governing the use of data, especially with regard to personal data. All of this means companies have to expend huge resources before seeing or realising a commercial benefit, which is why they often do not even attempt to generate new added value for customers by consolidating data from diverse sources. On top of that, many companies ask themselves whether they themselves would benefit at all from a data economy or whether they might ultimately suffer competitive disadvantages from giving up their data and while others capitalised on greater data mobility.

What can be concluded from these observations? The framework governing a data economy must be created in such a way that it gives all market participants equal opportunities. It should not further market asymmetries but instead help to eliminate existing imbalances. It should enable as many companies as possible to exploit the enormous potential of big data analytics and artificial intelligence. This will require an appropriate legal framework that promotes data sharing under fair conditions for all market participants. The goal should equally be to preserve trade secrets and the protection of personal data, thus strengthening data sovereignty.

The Association of German Banks believes the first step should be to create a European legal framework that enables data to be shared across different businesses and industries while taking a differentiated approach.

1. A cross-sector (B2B) data sharing framework should be established for personal and non-personal data. Businesses in all industries should be required to share the data provided to them by a natural or legal person via standardised mechanisms in real time if the person so requests. To safeguard a level playing field and preserve proprietary rights, care should be taken to ensure that this obligation applies only to data provided by the data subject and not to derived or refined data processed by the company. The latter category should be reserved for disclosure on a separate contractual basis. Further conditions will also need to be set with respect to aspects such as security and liability.

2. Existing technical and legal barriers to the exchange of non-personal data (= anonymised data, non-confidential business data) should be removed. This should be achieved, among other things, by creating greater legal clarity in areas such as anonymisation and, where necessary, easing data protection rules. Data cooperation in the form of data pooling, for example, is a major success factor for gaining new insights from the analysis of a wide range of data and for tapping the potential of artificial intelligence and machine learning for research and business in Europe. Ultimately, this also benefits consumers and society as a whole. Where corporate data are involved, it will continue to be the company in its capacity as the owner of a trade secret that decides whether or not to permit access to its data.

3. National and European open data strategies should rigorously promote access to public data. To this end, electronic access options should be established, interfaces with public data sources standardised and access points in the public sector consolidated to reduce transaction costs and make the data available for the broadest possible use. In some areas, the public sector could also take on the role of a central data intermediary by establishing a data exchange platform, especially in spheres where it operates corresponding central infrastructures to perform its public responsibilities.

To stimulate a European data economy, there is not least a need for appropriate collaboration platforms or forums that encourage dialogue between different sectors and stakeholders, promote the establishment of cross-sector data ecosystems and provide valuable impetus for the further development of a legal and institutional framework. The European Gaia-X[1] data and infrastructure platform is a promising example. This and similar initiatives should continue to be supported by policymakers and the public sector.

2. Starting point

Data are firmly at the heart of the digital transformation and they are becoming increasingly important as a key resource for the business models of today and tomorrow. They are the source of new insights, provide the basis for making forecasts and decisions, and thus generate essential added value for businesses and consumers alike. Data also have the advantage of not being consumed after use, allowing them to be used repeatedly and simultaneously by any number of different stakeholders. As digitisation progresses, there is a continuous increase in the availability of data (big data), allowing completely new added value chains and services to permanently change existing market and competitive structures. It is estimated that access to and joint use of data (depending on the level of data openness) will bring social and economic advantages of between 1% and 4% of GDP if public and private-sector data are taken together.[2]

These arguments suggest that Europe should seize the opportunities afforded by a data economy in order to regain lost ground in international competition and take a decisive step towards strengthening the continent’s competitiveness through data-driven innovation.

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the Second Payment Services Directive (PSD2) went a long way towards preparing the legal groundwork for the exchange of (personal) data in the European private sector. The background to these legal frameworks is, firstly, the intention to secure data protection in a modern information society and, secondly, the aim of creating more offers for data-based services. The GDPR introduced the right to the portability of personal data in order to give consumers greater control over their data and the manner in which they are used. The PSD2 opened up third-party access to payment data on bank accounts in order to increase competition and thus encourage more innovation. However, the current framework creates asymmetries in which some businesses – particularly the established non-European technology companies – act as data gatekeepers, while banks must allow unilateral access to their customers’ data. There is a lack of reciprocity here, which has a negative effect on Europe’s digital sovereignty.

Against this background, further development of the framework for the usage and exchange of data has rightly been placed high on the political agenda – at both European and national level. The proposals put forward in this paper are aimed at supporting the establishment of a future-looking and competitive data economy and identifying the measures required to further develop an EU data framework that places customer benefits centre stage. This will require taking account of the interests of all market participants and giving consumers, researchers, businesses and the public sector long-term added value.

3. Challenges

The current framework conditions make it impossible to achieve the desired goal of a competitive data economy for European businesses. In detail, these include:

- A lack of technical opportunities for individuals and businesses to transfer their data easily from one provider to another. The reason for this is the lack of standard, cross-sector interfaces for direct, secure and timely data exchange.

- Lack of opportunities for data processors to be able to consolidate data when access to other data is available. The reasons for this are heterogeneous data formats and the lack of identifiers for clearly assigning data to a person, a business or another data subject (e.g. a machine); standards therefore have a key role to play in further promoting the data economy, data interoperability and portability.

- Difficulties for businesses to take economic advantage of opening up their data to third parties. The provision of data incurs costs for businesses since they have to set up and maintain infrastructures as well as comply with legal requirements, including data protection, without being able to generate reliable income streams from the data themselves. This is particularly problematic when there is no reciprocity of data access or the varying quality of the data leads to market asymmetries and therefore to competitive distortion.

- The lack of a trustworthy and legally secure infrastructure with regard to data pooling and sharing. The broader a cross-company – or even cross-sectoral – data basis, the greater the likelihood of gaining new insights with the aid of artificial intelligence methods, for example.

- Lack of experimental spaces in Europe (sandboxes) to promptly seize on market developments, respond to customer requirements and bring innovations to market faster than was previously possible. This would require a legally secure environment for prototyping and developing new offers which would also give legislators and regulators the opportunity to identify relevant trends at an early stage and include these findings in the rulemaking process.

- Limited data availability due to data protection principles of data minimisation and purpose limitation. Currently, data may only be used if they are specifically needed to achieve a particular purpose. Yet modern services – including those promoted by PSD2 – aim at providing a comprehensive service for customers. As a result, the focus on purpose is increasingly “unravelling”.

- Lack of transparency and customer awareness as to what their data are being used for. Legally prescribed information requirements are not appropriate for data subjects, quickly lead to “information overload” and thereby weaken data sovereignty.

4. Relevance for the financial industry

The objective must be to overcome the above obstacles and unleash the potential of a data economy for the good of citizens, businesses, the public sector and society as a whole. This means data must be made easier to use – both within an organisation and also across companies and sectors. Not least banks and other financial firms could benefit from this.

But what kind of data are we talking about? The following chart offers examples of data from other sectors that might be relevant when it comes to exchanging data with the financial industry.

The following use cases highlight the customer benefits offered by selected data-driven banking solutions.

a) Identity services

A major asset of financial institutions is how much they know about their customers, ensured, among other things, by the need to meet regulatory requirements such as know-your-customer processes. This knowledge ranges from the verified identity of the persons involved to their creditworthiness and the detection of criminal behaviour such as money laundering. A careful evaluation of business partners not only reduces a bank’s own risk and fulfils government purposes but also generates valuable data of interest for business relations between the customer and other parties.

b) Promoting green finance/supporting sustainable customer behaviour

The financial sector has a key role to play in the transition to a more sustainable economy, especially by ensuring that finance is channelled into sustainable investment and that the production methods of corporate clients can be more environmentally friendly. But banks can also offer support for sustainable household management.

To steer capital towards sustainable investments, banks will in future be obliged, among other things, to take account of a customer’s individual sustainability preferences when providing investment advice. Together with the envisaged classification of all investment products according to sustainability criteria, this will ensure that banks can provide clients with suitable suggestions for financial instruments that meet their environmental, social and governance (ESG) preferences.

These preferences should not only be reflected in investment decisions but should also have an impact on other areas of lifestyle and housekeeping, such as energy supply, consumption behaviour or mobility use. As well as wanting to invest their assets sustainably, customers would also appreciate support making everyday decisions that affect their personal environmental footprint. Access to ESG-relevant consumption data on behalf of their customers would allow banks to calculate a corresponding footprint based on the customer’s individual lifestyle and mobility behaviour and thus satisfy this customer need.

New smart meters, for example, not only enable the measurement of current energy consumption but can also help to optimise consumption by determining the best times of the day and night to charge an electric vehicle or operate smart home appliances such as a washing machine or dishwasher. Such data could also be used to analyse a household’s consumption behaviour and to show the customer where savings could be made. Comparative data could be used, for instance, to forecast more reliably how energy retrofitting would affect the energy consumption of a residential property and determine whether state subsidies might be available for financing. In future, it would also be conceivable to offer loan agreements for hybrid vehicles or real estate with an interest rate dependent on the borrower’s energy consumption.

This shows how banks could assist their customers in making more sustainable choices beyond the question of how best to invest.

c) Holistic financial and investment advice

The objective of any financial adviser is to recommend suitable products for the client. And it is beyond question that targeted advice cannot be provided without a sufficient data basis. To enable advisory services to take as holistic a look as possible at the customer’s needs and preferences, it is helpful to have additional data, the type of which will depend on the customer segment, in order to deliver a better advisory experience and more tailored recommendations.

Today’s so-called multibanking services for consumers cannot guarantee that they are based on a sufficiently comprehensive view of a customer’s financial and life situation. In many cases, links between different providers fail to function due to a lack of standards for exchanging data or because they are not open to external access at all. The problem is that much more than the mere aggregation of banking data is needed to provide a truly holistic advisory service, including planning for old age. Information about all a client’s assets, liabilities, state and occupational pension entitlements, family data and personal preferences, interests and long-term plans should – and could – feed into holistic investment advice if only the relevant data could be accessed simply, quickly and securely with the client’s consent. The bank should therefore be able to agree with its clients what additional data to consider in the advisory process.

In the corporate client segment, too, more comprehensive financial advice could be provided to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), for example, by linking up different services. Many of these companies now use large online platforms to reach their customers. This relationship generates a huge amount of real-time data on items such as sales, inventories, customer ratings and returned items, which contain valuable information about the companies’ financial needs. With the help of these data, banks could provide SMEs with better support in managing their finances by optimising cash flow forecasts, for example, and thus reducing the company’s financing needs and allowing overall financial decisions to be made on a more informed basis. In addition, the bank could enable companies to offer customers the best possible payment option available at the time, thereby making their offers more attractive.

d) New financing and platform services

The continuing pluralisation and individualisation of our society are also reflected in customers’ expectations of products and services. “One-size-fits-all” approaches are increasingly falling out of favour, and this general trend goes for financial products too. At the same time, value chains are changing and more and more offers now cut across traditional sector boundaries or call them into question entirely. In consequence, the clear message for financial institutions is to focus on customer needs and the problem the customer wants to solve as well as the advantages he or she expects from a specific offer.

It is therefore conceivable that banks will in future build platforms and expand their range of solutions to include services that would today seem to have nothing to do with banking. Banks could thus help new ecosystems to emerge in areas such as the provision of capital goods and production capacities. As IoT technologies continue to gain ground in the production sector, banks could offer corporate customers new pay-per-use financing models. Sensors and digitally interconnected machines could be used to measure machine usage and production data in real time. Loan redemption rates could then be based on usage, making optimal use of liquidity and enhancing the customer’s financial stability. It would also be possible to identify the demand for certain production goods (screws, for instance) or the need for machine maintenance and relay the information to appropriate providers via online marketplaces. This would enable banks to help their customers achieve better capacity utilisation and improve their profitability.

e) Targeted contextual marketing

Data can help not only to make banking products and services more customised but also to offer them directly in the context where the customer need arises. Now that the smartphone has become a constant companion, this applies both online and at a physical point of sale. Using interaction and localisation data, offers can be tailored to the place and commercial environment in which the customer is active. The advantage for customers is that they can instantly access the products and services they need when they need them. If the relevant data are accessible to all, the customer will have a greater choice of providers and offers, which will indirectly result in more competition and more attractive services for the customer.

The prerequisite for this is that financial institutions and other market participants can operate in existing ecosystems and access relevant data and essential infrastructures – always with the customer’s consent, it goes without saying. This has the potential to counteract the dominance of platform providers and the loss of direct customer touchpoints.

For example, customers buying televisions from an online marketplace could be offered financing from their bank as soon as the sale is made, possibly offering an alternative to the dealer’s financing terms.

5. Concrete need for action

5.1 Facilitate a cross-sector exchange of data

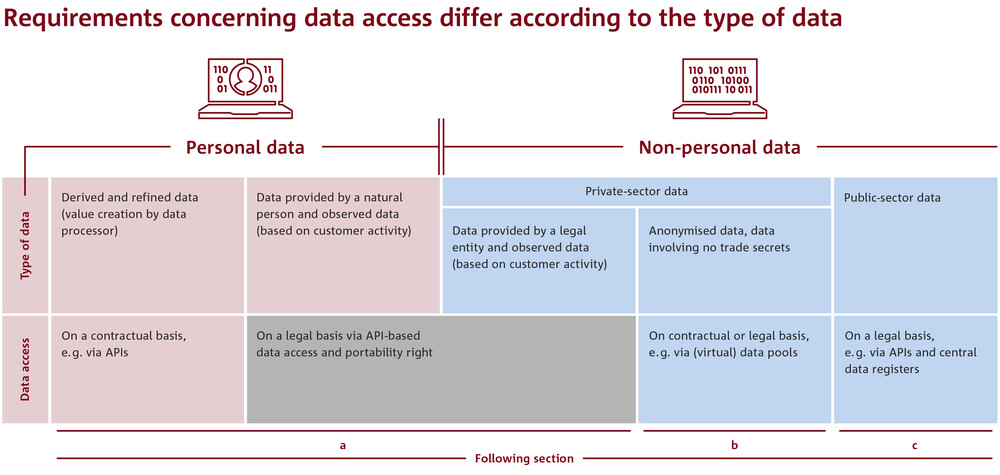

The European legal framework should be adjusted to enable individuals and businesses to use their data across all sectors. Given the diverse types of data and related rights of use, a differentiated approach is required. It is especially important to make a distinction between personal and non-personal data (= anonymised data and data of legal persons) as well as between raw and refined data (see chart below).

a) Data exchange framework for personal and non-personal data

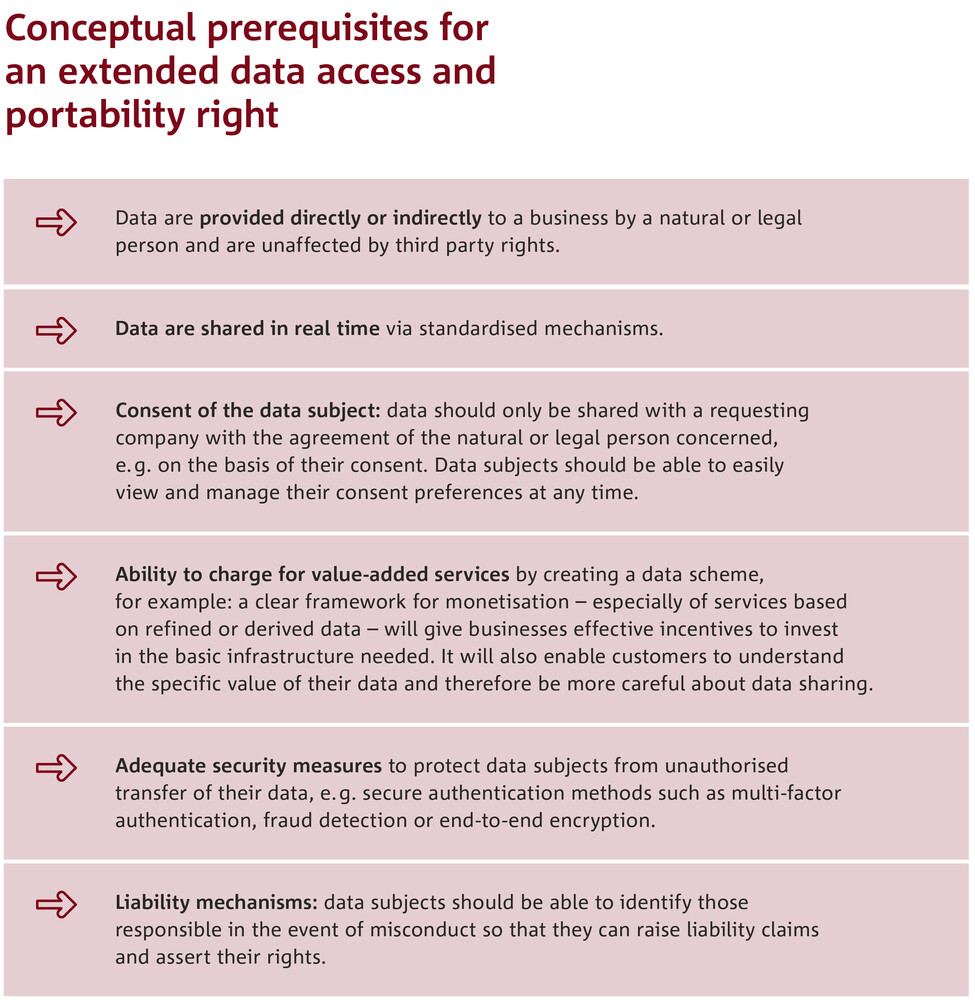

Customer interest must be the prime motivator for sharing customer data. The focus should be on customers and their needs and customers should benefit from data-based insights and possible innovations. This means that companies in all industries should be obliged to share data via standardised mechanisms in real time at the request of the natural or legal person concerned, provided that the data are not affected by third-party rights.

A natural person can already request that data they provide be transferred directly from one data processor to another. To enable this legal right to be exercised in practice and be reflected in new or improved products and services, it must be possible to transfer data in a standardised manner and in real time. In addition, the data must be transferred at the request of the data subject via a user-friendly interface so that the user can retain full control over the process. The right to portability of personal data introduced under the GDPR would then become effective and allow individuals to benefit from the economic value of their data.

This is not currently the case. It is true that the GDPR gives data subjects the right to receive personal data that they have provided to a controller in a structured, commonly used and machine-readable format and to transmit these data to a third party, provided that the data processing is automated (cf. Article 20 of the GDPR). As things stand, however, customers cannot benefit from the real added value of a cross-sector data exchange as the GDPR fails to spell out specific requirements for technical implementation.

The European Union should therefore establish a true cross-sector data exchange framework for consumers and businesses. This would enable data-based value creation to take place regardless of where the data were originally generated, and also reflect the increasing blurring of sectoral boundaries by providers and platforms operating in different sectors. Opening up access to data only within individual sectors would leave untapped the huge potential offered by cross-sector data exchange. On top of that, a heterogeneous data exchange framework focusing merely on a few sectors would risk exacerbating the uneven playing field which already exists as a result of PSD2. Given the increasing market penetration and diversification of non-European tech firms and platform operators, sector-specific approaches could further increase imbalances and undermine the competitiveness of European providers.

The proposal for a Digital Markets Act,[3] which is currently being discussed by European lawmakers, aims to address this competitive distortion between so-called gatekeeper platforms and other economic operators by granting the commercial and private users of these platforms urgently needed access rights to the data they generate there. This is a step in the right direction towards more data sovereignty and fairer competition. But it will be nowhere near enough to effectively leverage the far greater potential of a European data economy.

Like the right to personal data portability under the GDPR, a general right to data access and portability for natural and legal persons should, however, cover only data made available by end users or based on the observation of their activities.

By contrast, the provision of refined or derived data that companies obtain, recognise, transform, compute or verify on the basis of data supplied or observed must be a matter for individual agreements between the parties involved.

If the rights of the data owner will be affected, such as the right to protect trade secrets, the transfer or sharing of non-personal data should also require the consent of the holder of those rights.

A first step towards establishing such a cross-sector exchange framework could be to define a minimum data set and develop and implement corresponding standards. The scope of the data covered could be successively expanded. This would significantly reduce the effort and complexity involved in implementation and also shorten lead times.

b) Simpler access across different businesses and industries to non-personal data involving no trade secrets

To promote data-driven innovation for customers and strengthen financial stability by pooling risk or fraud-relevant data, for example, the conditions for sharing non-personal and non-confidential data across different businesses and industries should be improved. This is because more intensive use of data will enable not only new business models (based on pay per use, for instance) but also more targeted and tailored offers for customer. A broader data basis, such as a shared (virtual or distributed) data pool, will permit new insights to be gained with the help of artificial intelligence that cannot be obtained using traditional analysis. Additional (external) sources of data could, in addition, give rise to new customer segments that have not been served so far and thus contribute to greater financial inclusion by opening up access to credit, for example.

For various use cases, both regulatory and market-driven, the data held by one bank alone are often not sufficient to achieve desirable outcomes in terms of welfare economics: a larger data pool is needed. Take, for instance, lending to small peer groups. Pooling anonymised data from small groups could enable a critical mass to be reached that would allow providers to develop economically calculable products on more favourable terms, thus giving these customers access to loans.

When anonymised data are consolidated, there is nevertheless a risk of enabling certain data to be linked to a particular individual on the basis of the consolidated information, with the result that data protection rules would require their permission to be obtained. The exchange of anonymised data relating to groups of corporate customers, on the other hand, has the potential to affect trade secrets. Certain simplifications and legally binding rules would therefore be desirable to make it possible in these cases, too, to share or pool anonymised data in the event of a legitimate interest and for specific purposes without data-processing companies running the risk of violating data protection, antitrust or competition law.

c) Access to public data

Policymakers are already promoting the concept of “open data” by supporting the wide availability and reuse of public-sector information for private or commercial purposes. Provided, of course, that there are no or only minimal legal, technical or financial restraints. A major aim is to stimulate and promote the development of new services that combine and use the relevant data and information in innovative ways. The term “open data” is commonly understood to mean data that can be freely used, reused and shared by anyone for any purpose.

The German Open Data Act (Open-Data-Gesetz) requires public authorities in Germany to make open data available for further use. These data can be accessed via the data portal (in German only) and include anonymised statistics, federal budget data and numerous other metadata. They are made available to the public in formats designed to make further use much easier.

The EU’s Open Data Directive[4] marks a comparable step towards improving the availability of public data. Under the directive, all public-sector content (including that of public companies) which is accessible from documents is in principle available for further use – either free of charge or for a marginal fee. Special emphasis is placed on high-value datasets such as geospatial and environmental data, statistics, and company ownership and mobility data, all of which are considered to have significant potential for developing value-added services. Access is to be ensured via appropriate data formats and dissemination methods. High-value data, in particular, have to be made available in a machine-readable format via suitable electronic interfaces and, where appropriate, as a bulk download for further use.

Both legislative instruments have in common that they cover only data which are not subject to data protection or do not affect the rights of third parties (such as intellectual property or trade secrets). The European Commission’s proposal for a Data Governance Act[5] goes even further and sets a number of harmonised principles (such as non-exclusivity) under which public-sector data can be made available for reuse in situations where such data are subject to the rights of others. It does not, however, establish a right to reuse such data, but only sets out a framework which public-sector bodies should take into account. It also requires member states to establish a central contact point to assist businesses and researchers in identifying suitable data. The intention is to allow public-sector data to be accessed and used as effectively and responsibly as possible while enabling businesses and citizens to retain control of the data they generate and safeguard the investment made in their collection.

We warmly welcome these efforts to make the wealth of data available in the public sector more accessible for the benefit of the business community and society as a whole. The use of standardised data formats and application programming interfaces (APIs) is an absolute prerequisite for this, not least for enabling data to be transferred in real time. The European Commission should take a broad approach when it comes to defining what constitutes a “high-value dataset” so that the greatest possible potential can be exploited. To do so, however, it will be necessary to ensure not only that the data are always available in digital form but also that they can be accessed at a central location or via standardised interfaces. Due to federated structures and decentralised responsibilities, public databases and formats are currently highly fragmented – a problem which urgently needs to be overcome, nationally at least as an initial step and in the medium term at European level.

As part of a comprehensive open data strategy, the public sector should also make sure that its citizens can easily share certain publicly held data concerning them with third parties. This would, for instance, enable citizens to make their state pension scheme data available to their financial adviser as the basis for improving tailored planning for old age. The example of a digital pension dashboard makes it clear that there will only be a benefit for citizens when data from different sources are consolidated – in this case their entitlements from statutory, occupational and private pension schemes. If the state obliges further pension providers to submit their data to a central location, as is intended under the German Digital Pension Overview Act,[6] third-party service providers which meet certain minimum criteria should also be given direct access to these data via a digital interface. This will enable them to offer additional value-added services to the persons concerned.

As part of its digital finance strategy, the European Commission is considering the idea of promoting common technical standards to facilitate access to banks’ financial and regulatory data which are already subject to mandatory disclosure. Examples mentioned are financial and non-financial reporting data, regulatory disclosures and information documents for investment products. The obligation to disclose financial reports and ESG data, for example, applies not only to financial institutions but also to businesses in the real economy. Access to these data should be facilitated by setting up central digital repositories. Financial institutions, especially, would find it extremely useful if firms in the real economy fed their ESG data into a data register along these lines. To achieve this, the EU could support the development of a central data register to make it easier to establish an open source of ESG disclosures and allow access to relevant and reliable data at EU level (ideally in a standardised form, but also with access to disaggregated raw data). In addition, it should open up its own databases of information on environmental reporting, among other things, and make these data available for reuse by financial service providers via the central repository. Furthermore, Eurostat’s data sources should also be made reusable for financing purposes.

Care should be taken to ensure that only data intended for public disclosure are openly accessible. There are good reasons why these make up only a part of the data that the financial sector shares with its competent authorities for supervisory purposes.

Equal caution should be exercised when public authorities significantly expand access to private-sector data on the grounds of public interest, as is currently being considered by the European Commission in the context of its upcoming proposal for a Data Act. The hoped-for benefits, such as the ability to improve public transport, make cities more environmentally friendly, fight epidemics and develop more evidence-based policies, must be carefully weighed against the associated burden on businesses. Given the scale of existing reporting and disclosure obligations, policymakers should be aiming to reduce them and not increase them further by imposing additional requirements. Instead of introducing new rules, priority should be given to setting incentives for businesses to share data with the public sector voluntarily. Such incentives could, for example, take the form of tax breaks, public recognition or better use of the data through co-creation with public institutions. In view of the fact that different economic sectors and actors will be affected to differing degrees, it would in any event be desirable in the interests of fairness to reimburse companies for the infrastructure costs they incur when transferring data to the public sector.

5.2 Technical prerequisites for exchanging data

To ensure that their joint use is straightforward and produces useful information, data should be exchanged in real time, in common formats and with defined transfer mechanisms, such as APIs, that comply with agreed standards and taxonomies. Some providers already offer cloud-based solutions that enable a fast, standardised API rollout (e.g. APIGee).

In the medium to long term, consideration should be given to using more advanced technologies such as distributed ledger (blockchain) technology, artificial intelligence or synthetic data. This is because, firstly, these technologies will enable customers to monetise their own data autonomously and independently. Secondly, they will make it possible to effectively improve micro and macro-supervision, reduce development costs and regulatory burdens and facilitate the entry of new companies.

Building on experience in Sweden, for example, the development of smart contracts for buying property could be promoted in Germany and subsequently throughout Europe in cooperation with notaries, land registry offices, brokers and banks. The Swedes have developed a blockchain-based cadastral system in an overarching project involving authorities, banks and other businesses.[7]

5.3 Accompanying standardisation and collaboration platforms for the cross-sector exchange of data

An exchange platform should be established to promote data exchange between various sectors and thus move towards a functioning data ecosystem. The current development of an interconnected European data and infrastructure ecosystem (Gaia-X) points in the right direction and could perform this function. Gaia-X has the potential to foster the emergence of cross-industry projects and, where appropriate, serve as a governance body for agreeing and further developing common standards for the exchange of data. A collaboration and governance platform along these lines should be closely interlinked with corresponding national platforms to support consistent Europe-wide development and ideally provide impetus beyond Europe for the emergence of a global data ecosystem.

[2] OECD (2019), Enhancing Access to and Sharing of Data: Reconciling Risks and Benefits for Data Re-use across Societies, OECD, https://doi.org/10.1787/276aaca8-en.

[3] Proposal for a REGULATION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL on contestable and fair markets in the digital sector (Digital Markets Act), COM/2020/842 final

[4] DIRECTIVE (EU) 2019/1024 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 20 June 2019 on open data and the re-use of public sector information

[5] Proposal for a REGULATION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL on European data governance (Data Governance Act), COM/2020/767 final

[6] Gesetz zur Verbesserung der Transparenz in der Alterssicherung und der Rehabilitation sowie zur Modernisierung der Sozialversicherungswahlen und zur Änderung anderer Gesetzte (Gesetz Digitale Rentenübersicht) of 11 February 2021 (in German only)

[7] https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5e26f18cd5824c7138a9118b/t/5e3c35451c2cbb6170caa19e/1581004119677/Blockchain_Landregistry_Report_2017.pdf