Action required to make better use of cloud technology

Digitisation has been a key topic for many years now and it is one to which the Association of German Banks is fully committed, having organised numerous related initiatives, projects, events and publications.

1 Executive summary

Shaping the digital future and ensuring digital competitiveness are among the key challenges we face in the coming years, which is why they are high on the agendas of many stakeholders. In its digital strategy, the European Commission has laid out its intention to develop Europe into a global pioneer in this area and to focus on the benefits of digital technologies for the good of its citizens. Digitisation has been a key topic for many years now and it is one to which the Association of German Banks is fully committed, having organised numerous related initiatives, projects, events and publications.

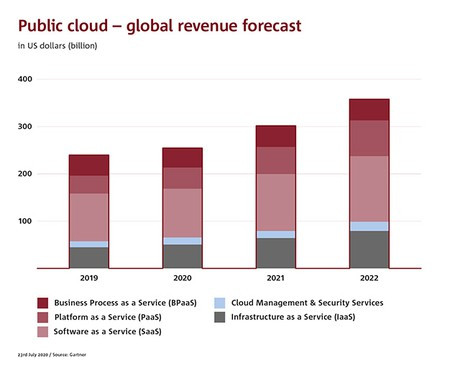

Cloud computing plays a vital role in this context and, as such, forms the technological foundation for the digital future. Not only has the use of cloud services exploded in recent years, this trend is forecast to continue for some time to come (see diagram).

Cloud technology and the outsourcing of data processing in the cloud are becoming increasingly important across a number of sectors. However, the focus is less on whether processes and services should be outsourced and more on how the cloud can best be used to fully exploit its expected potential.

This position paper looks to identify existing challenges in the banking sector and puts forward concrete recommendations to tackle them. It is therefore aimed at those drawing up legislation, setting standards and making rules as well as the supervisory authorities. Its aim is to intensify the dialogue amongst stakeholders in order to remove today’s hurdles as quickly as possible, thus enabling banks to use the cloud technology more widely.

We are proposing 13 recommendations based on an examination of the four areas in which a need for action has been identified: concentration of providers, regulation, data protection/third country transfer and audits.

- Promote European IT cooperation projects and help establish a competitive landscape of European providers of cloud services.

- Have supervisory authorities assess the viability of services developed for financial service providers as part of the Gaia-X initiative before they are made available.

- Intensify dialogue between regulators, supervisory authorities and the banking industry on the European Commission’s proposed voluntary standard contractual clauses for agreements between financial service providers and cloud providers.

- Develop cross-industry standards, including suitable security standards, as a prerequisite for basic data portability between cloud providers and to guard against vendor lock-in.

- Further harmonise banking supervision legislation, particularly when it comes to requirements for reporting to supervisors and for exit strategies in order to reduce the complexity of a large number of regulatory requirements.

- Standardise the different terms and sometimes contradictory definitions from the various regulatory requirements, which often lead to differing interpretations when it comes to their practical implementation.

- Take a risk-based approach in defining the requirements for cloud outsourcing. Not all outsourcing to the cloud results in increased risk.

- Develop a standardised electronic transfer mechanism for reporting outsourcing and third-party agreements, which currently differ across Europe and are based on manual processes.

- Have EU supervisory authorities take a leading role in cross-border dialogue to prevent go-it-alone approaches by individual states, particularly when it comes to regulations concerning data storage locations.

- Intensify the exchange of information between supervisory authorities, financial institutions and cloud providers on the importance of cloud use and its acceptance in risk assessment and audit practices.

- Have EU legislators develop a solution which allows the practical implementation of requirements to guarantee the protection of data when transferring it to third countries. The use of US-based cloud providers, in particular, and the associated data transfers to the US require practicable and standardised instruments that give cloud providers and cloud users legal certainty and offer robust guidelines for the protective measures needed.

- Use an internationally standardised set of monitoring criteria for auditing the requirements to be met by banks when outsourcing services to cloud providers.

- Option to commission an external cloud auditing expert to conduct audits based on a uniform and standardised set of monitoring criteria.

2 Initial situation

The information technology (IT) at many banks has been subject to a paradigm shift for some years now. Given the rapidly changing demands of the market and of customers, a flexible and powerful IT infrastructure has now become essential for banks to remain competitive. One area that has become crucial in achieving this objective is the use of cloud technology. It allows banks to operate a highly flexible IT infrastructure that supports innovation at manageable cost.

In terms of IT architecture, most banks are aiming for a hybrid mix of traditional IT systems and cloud applications. One important element in achieving this aim and securing a bank’s competitiveness is the targeted migration of bank infrastructure from local systems to the cloud.

2.1 An overview of cloud services

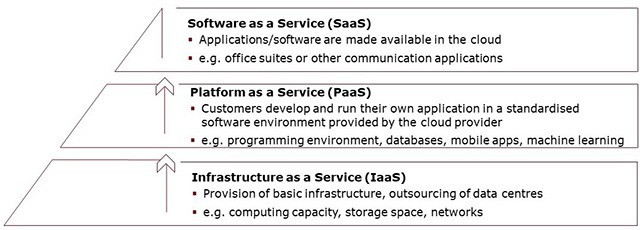

Many banks today have already dipped their toes into the world of public cloud solutions, i.e. they use storage and computing capacities at data centres made available by cloud providers. In addition, there are an array of different services available depending on the type and scope of the service being outsourced. They range from flexible storage capacities (IaaS) to platform services (PaaS), the use of tools for analysing large amounts of data in the cloud and entire software programs implemented from the cloud (SaaS) (see diagram).

In a multicloud environment, multiple cloud computing and storage services from several cloud providers can be bundled together to make use of the various offers as efficiently as possible.

2.2 The impact of cloud services on the financial sector

The use of cloud technologies by banks will, depending on the scope, not only affect bank IT, but will also impact the entire organisation, its workflows and processes. The increased agility and scalability will improve, for example, the time to market for apps and IT-driven bank products.

Cloud services also serve as the technological foundation for analysing large quantities of data, as is required for artificial intelligence (AI), for example. They also allow banks to use their resources more efficiently because they no longer need to reserve additional computing capacities locally for peak loads. This reduction in local computing capacity in turn means reduced capital investment. Cloud service providers can assist with their data centres, which provide a high degree of IT professionalisation and standardised operating procedures.

2.3 Cloud initiatives

There are now a number of different initiatives on the European market aimed specifically at addressing the issues arising from cloud services, e.g. Gaia-X, Switching Cloud Providers and Porting Data, the Collaborative Cloud Audit Group and the European Cloud User Coalition.

2.3.1 Gaia-X

Gaia-X is based on a joint initiative of Germany’s Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and France’s Ministry of the Economy and Finance. The aim is to develop joint requirements of a European data infrastructure in order to create a trustworthy ecosystem of networked, decentralised infrastructure services. Data from these services can then be made available and shared securely and confidentially, in accordance with European values.1To achieve this, 22 member organisations founded the Gaia-X European Association for Data and Cloud AISBL, an international non-profit association under Belgium law.2Accordingly, the association’s work focuses on user ecosystems and user requirements in various domains with an emphasis on individual sectors. For example, the financial sector in Germany is mainly supported by the Financial Big Data Cluster project.

2.3.2 Switching Cloud Providers and Porting Data (SWIPO)

SWIPO AISBL3is an alliance of various stakeholders supported by the European Commission which develops and administers voluntary codes of conduct for the proper application of EU Regulation 2018/1807 on a framework for the free flow of non-personal data (Article 6, Porting of data). The codes of conduct are aimed at preventing or removing the occurrence of cloud vendor lock-in (dependence on one provider). The codes and associated governance documents and procedures have already been finalised and published.4The organisation is under no direct influence from the European Commission and consists of cloud providers and cloud service users.

2.3.3 Collaborative Cloud Audit Group (CCAG)

The Collaborative Cloud Audit Group is a sector-wide initiative that performs pooled audits of cloud providers to ensure compliance with the material outsourcing operations of financial institutions and insurance companies. It was founded by Deutsche Börse in 2017. The group reduces the costs and complexity of auditing cloud providers by forming several teams of financial institutions whose employees conduct pooled audits of cloud providers.

2.3.4 European Cloud User Coalition (ECUC)

In January 2021, 12 financial institutions founded the European Cloud User Coalition. Its aim is to promote the use of public cloud systems across the entire European financial sector. To achieve this, the financial institutions represented in the initiative have compiled a list of best practices and joint security standards for cloud providers to comply with. These should enable better implementation of Europe’s high regulatory and data protection standards, also for non-European cloud providers and, in the long term, allow financial institutions to be more independent in their choice of technology.

3 Areas requiring action

3.1 Concentration of providers

3.1.1 Promoting a competitive European cloud infrastructure

Europe’s digital sovereignty is vitally important for the innovativeness of European businesses and organisations. Users of IT services and of success-critical digital technologies are reliant on there being adequate competition among providers. As users of a variety of IT services for many years, banks are all too aware of this.

Recommendation: A competitive European landscape of IT cloud providers and European IT collaboration projects, such as the Gaia-X initiative, is very important and must be sustainably promoted. The initiatives add to the sovereignty of Europe’s digital infrastructure and contribute to greater independence from global political risks. It is also important to guarantee the European level of data protection and ensure that services remain trustworthy.

3.1.2 Supervisors must recognise regulatory compliance of Gaia-X services

The market for cloud infrastructure is currently dominated by a small number of large global providers. In order to minimise the resulting dependency, solutions are required that continue to enable banks to cooperate with these providers, but which also offer more flexibility. The Gaia-X initiative is already looking at this aspect. Usage scenarios were analysed and evaluated for a wide range of sectors – including finance – in order to detail the requirements of a European data infrastructure in more concrete terms. These usage scenarios are published and put into practice without any prior evaluation by the competent supervisory authorities.

Recommendation: All financial services bearing the Gaia-X label should already have been given the green light by supervisory authorities prior to release. Gaia-X could thereby help to ensure that the regulation of cloud services better reflects the requirements of the financial sector.

3.1.3 Standardising cloud service agreements

Both in terms of banking supervision and data protection, cloud service agreements between cloud providers and banks as cloud users are becoming increasingly important because the content of these contracts determines whether or not a financial institution is still complying with regulatory requirements if it outsources the processing of its data to the cloud. When negotiating these agreements, cloud providers must first gain an understanding of the much higher regulatory requirements for cloud outsourcing in the financial sector compared to other industries. However, getting global providers with their considerable market power to accept bank-specific requirements is somewhat of a challenge.

Partially standardising cloud agreements would therefore simplify negotiations between cloud providers and customers. At the same time, these standardised agreements would provide supervisory authorities with a uniform basis for evaluating contractual relationships where cloud services are outsourced. It should be noted, however, that cloud projects can differ widely on many aspects – for example, in terms of scope, service level and internationality. It must therefore remain possible for contract partners to make contractual agreements that are tailored to each specific case, which generates a degree of tension between standardisation and freedom of contract.

Recommendation: The European Commission has been working on voluntary clauses for cloud agreements in a variety of areas for two years now. Recommendations from the European banking industry should be given proper consideration here. It is necessary and would be sensible for the European Commission to communicate its proposal for new standard clauses for data protection, which were published in June 2021, to European and national banking supervisors. The aim would then be to conduct further joint discussions with the European banking industry about these voluntary standard contractual clauses. In determining regulatory compliance, standard contractual clauses should be considered reference clauses by supervisors. Particular importance should be given to the parts of the contract relating to auditing rights for customers and reporting obligations on sub-outsourcing by cloud providers.

3.1.4 Data portability to prevent vendor lock-in

Cloud providers rely on the use of proprietary technologies for numerous cloud services on the market today. From the provider’s point of view, this is done to differentiate their offers from those of their competitors and promotes customer loyalty. However, the data stored in the cloud and/or services used in the cloud can often not be transferred to another provider. It is therefore vital to develop cross-industry standards in order to ensure the basic portability of data between different cloud providers. This could be an effective way of making the cloud market more transparent and increasing the pool of cloud providers.

In addition, guidelines from the European Banking Authority (EBA) on outsourcing arrangements (EBA/GL/2019/02) require financial institutions to have an exit strategy in place when outsourcing critical or important functions as part of their risk analysis. Among other things, the guidelines stipulate that institutions must be able to withdraw outsourced functions and data from cloud providers in order to transfer them to another provider or to incorporate them into their own systems.

Recommendation: Automated processes are required to prevent vendor lock-in effects. It is therefore important to promote standards on data formats and the corresponding data transfer interfaces. The standards would also have to include suitable security specifications. Cloud providers could also provide a standardised interface (Application Programming Interface, API) for importing and exporting the stored data, as well as services for proving the completeness of the import/export.

3.2 Regulation

3.2.1 Harmonise banking supervision law

The current regulatory environment only allows banks to make optimal use of cloud technology to a limited extent since today’s banking regulation is insufficiently geared towards bank-specific use of the cloud. The rules and regulations are complex and to be found in a variety of sources.5A bank needs to conduct extensive analysis and evaluation to determine beyond all doubt precisely what requirements it must comply with. Unless the existing rules and regulations are standardised and simplified, any additional new policy approaches will further increase complexity and costs without significantly reducing risk.

The Digital Operational Resilience Act (DORA) proposed by the European Commission would certainly harmonise IT security regulation in the financial sector. As a “lex specialis”, DORA would act as a comprehensive and thus sole means of regulating financial institutions in this area. The intention is to harmonise the numerous existing regulatory approaches and provide a uniform set of rules which apply across borders, thus avoiding differing national implementation. The objective of this initiative is correct and in the banks’ interests. However, it remains to be seen what the outcome of the legislative process will be. DORA can only make a partial contribution to the further harmonisation of banking supervisory law.

Recommendation: We continue to call for harmonisation of banking supervision law – ideally at EU level – and the establishment of standards. In particular, the requirements for reporting to supervisory authorities and for exit strategies (e.g. business continuation if an outsourcing agreement is terminated or in the event of significant service failure, etc.) should be clear and uniform across Europe.

3.2.2 Standardise terms and definitions

The different requirements of regulators have led to divergent and sometimes contradictory definitions and criteria. Differing definitions exist for terms such as “outsourcing”, “third party relationships”, “information technology services” and “cloud services”. When implementing the requirements in a global environment, this results in unnecessary complexity, substantial costs and additional problems meeting deadlines.

Recommendation: The terms and definitions used in different regulatory requirements should be standardised in order to avoid different interpretations when implementing the requirements and carrying out subsequent audits. Thresholds and criteria for criticality/materiality and outsourcing must be consistent.

3.2.3 Support a risk-based approach

Today’s requirements for cloud outsourcing are not sufficiently risk-based and, as a result, frequently disproportionate. In our view, cloud services should not be automatically regarded as outsourcing, but only when analysis has explicitly shown this to be the case. Not every outsourcing to the cloud generates increased risk for a bank: take, for instance, a situation where canteen plans or lists of office material suppliers are stored in the cloud. Blanket classification as outsourcing may also be due to a lack of experience on the part of supervisors and financial statement/IT auditors when it comes to assessing the benefits and drawbacks of the cloud from a risk management perspective.

Recommendation: The regulation and supervision of cloud outsourcing should always take a risk-based approach. It is essential, to this end, for banks and supervisors to have a common understanding of the risks and available control mechanisms associated with cloud services. The assessment of the risks involved should be based on common criteria, such as the degree of transfer of responsibility and the criticality of the outsourced data and functions.6We recommend establishing EU-wide rules and standards.

3.2.4 Standardise electronic transmission of reporting files

Content requirements and data standards for reporting outsourcing and third-party agreements are fragmented in Europe. The same goes for the maintenance of outsourcing registers. What is more, they are based on manual systems and processes, which are consequently prone to errors.

Recommendation: We suggest that banks should be involved in standardising the reporting of third-party agreements, with common data standards and interfaces (APIs) becoming the norm.

3.2.5 Easing national rules on where data should be stored

When operating on the international stage, banks often face national rules requiring data to be stored or processed locally. These generate additional costs and obstacles to innovation without any corresponding benefit in terms of helping to achieve regulatory objectives. On top of that, rules on local storage and processing have a detrimental effect on the ability of financial institutions to make full use of the cloud. They result in a more complex IT architecture and may even create new information security risks.

Recommendation: European supervisory authorities should assume a leading role on the international stage in promoting a more extensive exchange of information between regulators and supervisors with the aim of avoiding negative consequences when individual countries go it alone. Requirements to store or process data locally should be avoided. In particular, direct access by supervisors to data held by cloud service providers on behalf of banks should be done in such a way that ensures banks can comply with banking secrecy and data protection rules.

3.2.6 Promote acceptance of cloud use among supervisors

There is nothing new about the outsourcing of services in the banking industry. But use of the cloud is a special form of outsourcing and sometimes requires specific expertise when it comes to risk assessment and audit practices. This expertise is yet to be acquired in some areas.

For example, not all national and international supervisory authorities support the idea of pooled audits even though these are already permitted under the EBA Guidelines on Outsourcing (see also the Collaborative Cloud Audit Group’s initiative on pooled audits).

Recommendation: Supervisors, financial institutions and cloud providers should step up their exchange of experience and views so that the risks and opportunities of the cloud can be adequately assessed and safe migration to the cloud can be supported. In particular, banks and supervisory authorities should work together to advance the initiatives of the CCAG on possible pooled audits in order to pursue the best possible approaches and solutions to auditing cloud services.

3.3 Data protection and third-country transfers

Data protection law becomes relevant if personal data are to be processed in the cloud. This is information about natural persons. It does not cover other types of data (e.g. information about legal entities). Banks must nevertheless observe banking secrecy.

The use of a cloud provider is normally classed as contracted data processing under data protection law. Article 28 of the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) stipulates that a processing agreement has to be concluded between the client (cloud user) and the contractor (cloud provider). In particular, this agreement must give the client the right to issue binding instructions to the contractor so that the former remains “master” of the data. For some cloud providers, even this requirement can be a challenge.

Compliance with data protection law becomes significantly more complex and problematic if the cloud service provider is based in a third country (= countries outside EU/EEA). While it does not matter where the provider processes personal data within the EU/EEA, special requirements must be met when processing data in a third country. Under the GDPR, personal data may only be transferred to countries outside the EU if

- the data subject has consented,

- the transfer is necessary for the performance of a contract (e.g. so that a payment can be made in the US) or

- an adequate level of data protection exists in the third country.

Under EU law, a third country is assumed to have an adequate level of data protection in the following cases, among others:

- The European Commission has explicitly recognised the third country as having an adequate level of data protection (examples of “safe” third countries: Switzerland, Japan).

- The transferring company in the EU and the company based in the third country have agreed on EU standard contractual clauses (often the case when using third-country data centres for processing).

- Binding corporate rules (BCRs) have been adopted for internal data transfers within international companies/groups.

- A US company has committed in its capacity as data recipient to comply with the EU-US Privacy Shield (formerly the Safe Harbor Agreement, which was struck down by the European Court of Justice’s “Schrems I” decision).

In summer 2020, the data protection situation with respect to third countries became even more serious. In its ruling of 16 July 2020 (Case C-311/18, “Schrems II”), the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) declared the European Commission’s adequacy decision on data transfers to the USA (EU-US Privacy Shield) to be invalid. Data protection authorities in the EU have inferred from the ruling that the EU standard contractual clauses adopted by the European Commission to protect data transfers to certain third countries (such as the US) can now only be used if additional safeguards are in place. Owing to the allegedly extensive rights of US authorities (especially US intelligence services) to access databases in the US, some data protection authorities doubt whether it is possible at all to agree sufficient safeguards with a service provider if data are to be processed in the US. There is thus a danger that all transfers of personal data to the US could be declared illegal. Trade associations at national and European level (including the Association of German Banks and European Banking Federation) have publicly highlighted the associated implementation problems and the insoluble nature of the dilemma and stressed the need for political action.

This places companies in a quandary since transferring data to the US is common practice, especially when using cloud services. In addition, companies must now negotiate with their business partners on a case-by-case basis and can no longer make ready use of the European Commission’s standard data protection clauses, which were intended to be universally applicable. It will be important to take a risk-based approach and find solutions which can be standardised. The safeguards put in place to ensure an EU level of data protection in dealings with third countries should be proportionate to the risk identified in each individual case. Measures should be necessary, appropriate and proportionate in light of the circumstances involved and the potential associated risk. In addition to contractual and organisational safeguards, technical safeguards (such as encryption) will also have an important role to play. With adequate safeguards in place, it should remain possible for companies to rely on the European Commission’s standard contractual clauses on data protection when transferring data to third countries.

It is unclear as things stand whether and when regulators will find a practicable (political) solution. An example of a sound approach is the decision taken by the European Commission on Brexit in June 2021, under which the level of data protection in the United Kingdom will be deemed adequate for the next four years. The start of negotiations between the European Commission and the US administration in March 2021 on a successor to the EU-US Privacy Shield is also an important step towards re-establishing legal certainty and practicable instruments for guaranteeing data protection.

Recommendation: Banks wishing to use cloud services need planning and legal certainty with respect to data protection law. Until now, this certainty has been ensured by instruments such as the EU-US Privacy Shield and EU standard contractual clauses. These proved practicable, not only for large companies but also for small and medium-sized businesses with limited resources for legal advice. The current tendency to make companies shoulder the burden of carrying out detailed analyses of the data protection situation in third countries makes it virtually impossible to use third-country cloud service providers.

In the wake of the CJEU “Schrems II” ruling of July 2020, there is an urgent need from the perspective of the entire real economy for lawmakers to make standardised instruments available at EU level that give cloud providers and cloud users legal certainty and provide robust guidelines for the safeguards required when dealing with certain third countries. It is absolutely essential to take a risk-based approach. The new standard contractual clauses on data protection unveiled by the EU Commission in June 2021 are an important step in the right direction. It is nevertheless a suboptimal strategy to put the onus of checking data protection adequacy solely on businesses and other organisations that depend on data transfers to third countries.

3.4 Make audits of cloud providers more efficient

Financial institutions which outsource their IT needs monitor how service providers comply with the requirements placed on them. Auditing cloud service providers poses special challenges. The checks that have to be carried out by individual financial institutions at individual cloud providers are time-consuming and costly, tie up resources, generate additional risks and ultimately make it more difficult for financial institutions to access cloud services. To make auditing cloud providers more efficient, alternative ways of furnishing proof of compliance should be used.

3.4.1 Standardised catalogue of requirements

When outsourcing, financial institutions define various requirements for the outsourcing process. These include bank-specific requirements for dealing with the third-party service provider and also requirements that the IT service provider has to fulfil. Most of the IT security requirements set by many banks are the same since they concern fundamental aspects of IT and information security.

Recommendation: With the help of a monitoring catalogue based on internationally recognised standards, the requirements set by financial institutions for cloud providers could be checked in a quantitatively and qualitatively consistent manner and corresponding proof of compliance could be provided. The Cloud Control Matrix would lend itself to this purpose. Any additional requirements could continue to be addressed by financial institutions individually.

3.4.2 Proof of compliance provided by a central auditor

Each financial institution verifies whether the requirements specified in its monitoring catalogue have been implemented and complied with. It asks the cloud provider to supply the necessary evidence of compliance (e.g. in the form of ISO certifications) or carries out its own on-site inspections if it is able to do so. This evidence is consolidated with in-house checks. The financial institution then compiles the results of both the in-house audit and that of the cloud provider and makes them available to its supervisory authority. Audits of cloud service providers are currently carried out by each bank individually or in the form of pooled audits (see Collaborative Cloud Audit Group). The latter option means banks and cloud service providers have to invest fewer resources in audits but the amount of time and effort involved is still high. If compliance with the common requirements set out in the standardised monitoring catalogue were checked by a single (central) auditor on behalf of several banks, this would increase efficiency and ensure high-quality results.

Recommendation: Banks should have the option of commissioning a central auditor to audit compliance with those outsourcing requirements set for cloud service providers contained in a standardised set of monitoring criteria. The auditor could then make the results of the audit available to several banks as well as to the competent authorities on the banks’ behalf. Using a single, standardised monitoring catalogue and having audits performed by auditors with cloud auditing expertise would deliver comparable results of sustained high quality (based on internationally recognised security standards).

4 Outlook

The trend towards cloud use will continue to gain pace, also in the years to come. The corona crisis has only strengthened this trend. It is unlikely that the rapid transition to working from home and the use of digital service providers would have been possible in such a short space of time without flexible cloud-based solutions. In future, more and more applications will be accessed from the cloud as part of the further digitisation of business processes.

However, in order to fully benefit from the potential of this technology, we need to remove today’s hurdles. Legislators are being called upon to provide legal certainty on data exchange with third countries, to further harmonise banking supervision law and to define voluntary standard contractual clauses. It will also be important to develop and have supervisory bodies recognise standards relating, for example, to automated processes for data portability, to the electronic transfer of reports to supervisory authorities and to reviewing bank-specific outsourcing requirements for cloud providers.

Furthermore, banks are still subject to competitive disadvantages over technology companies. Current banking regulation is aimed at financial institutions as a whole and is therefore institution-based. If banks or financial institutions account for more than half of certain key figures (capital, assets, turnover, number of employees, etc.) in a group, all the banks, financial institutions and ancillary service providers are subject to banking regulation even though other units of that group may offer, for example, technology services as ancillary service providers. However, banking regulation does not typically apply to technology companies offering financial services on a smaller scale. This results in an imbalance in terms of obligations to comply with certain regulations.

Placing greater demands on banks, which, for example, makes the integration of external technologies and therefore the dismantling of legacy systems more difficult, will stifle further digitisation initiatives, thus complicating the whole process of digitising the financial sector. This will have a negative impact both on the innovative power of the banks and on their ability to contribute to Europe’s digital sovereignty.

Instead, regulation and supervision should target the activities of a company. This would mean taking more of a risk-based approach, which would also apply to new financial market participants (technology companies). Effective regulation must therefore focus more on the processes that are particularly relevant from a risk perspective and less on the company that provides them.

1 https://www.bmwi.de/Redaktion/EN/Dossier/gaia-x.html

3 AISBL: legal form for international non-profit organisations under Belgium law.

5 For example, EBA/ESMA guidelines on (cloud) outsourcing; the European Network and Information Security Directive (NIS Directive); BaFin’s Minimum Requirements for Risk Management (MaRisk); BaFin’s Banking Supervisory Requirements for IT (BAIT); BaFin’s Guidance on Outsourcing to Cloud Providers; the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

6 See chapter 4.2 of “The use of Cloud Computing by Financial Institutions” by the European Banking Federation from June 2020 (https://www.ebf.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/EBF-Cloud-Banking-Forum_The-use-of-cloud-computing-by-financial-institutions.pdf)

Contact